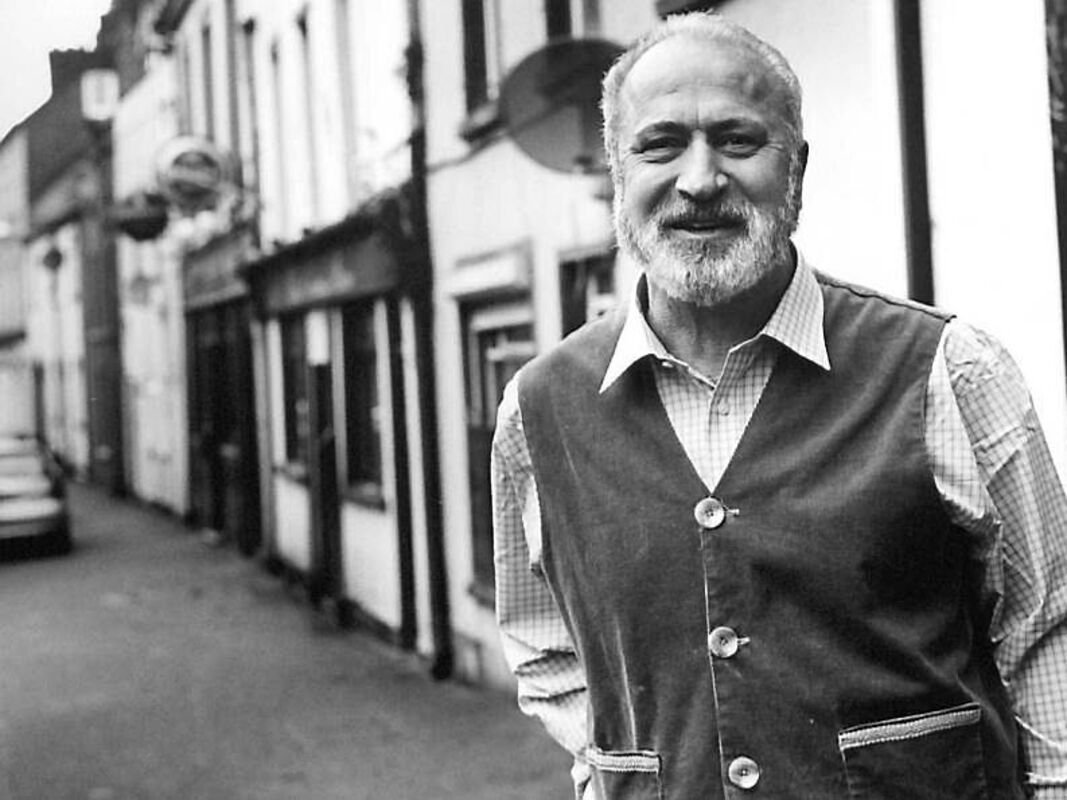

C. K. Williams on Antisemitism

One of the crises facing Jews in America today is antisemitism. For much of postmodern times, antisemitism has seemed rather deeply recessive. American Jews have lived in a nation where to be a Jew was, most often, neither particularly noteworthy nor exceptional. For some Jews, intermarriage and assimilation were major issues. But for most Jews and most Americans, being Jewish was not a particularly large problem.

Percy Byshhe Shelley: “Ode to the West Wind”

When I was in college, I and my roommates loved to make fun of Shelley. His deeply un-self-conscious self-description cracked us up. “I fall upon the thorns of life! I bleed!” We were so eager to get on with our lives, so caught up in the need to be self-confident and secure, that Shelley was an embarrassment. And those exclamation points! What could be more, well, ‘uncouth.’ Oh, and we so much wanted to be ‘couth.’

Greg Delanty, “Attachment”

Poems are strange things. Every once in a while – fairly rarely, it seems to me – something stands before us and we are amazed or, as the Brits would say, gob-smacked. The world is otherwise than it was before. We know more, understand more, see more.

These letters, near their very beginning, dealt with a poem by Eugenio Montale [type ‘Montale perhaps one morning’ in Google], in which a man turns around and the whole world which seems so concrete to us just falls away. He turns so suddenly that there is nothing behind him, “nothing at my back.” Wallace Stevens says the same thing of a snow man, who sees “Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.”

Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73

No one who writes about poetry in English can avoid Shakespeare. Arguably the greatest writer the world has seen, he is best known for his dramas: Tragedies, comedies, histories. But he also wrote a remarkable poetic sequence, of sonnets. Many of them, I confess, are beyond me: Try as I might, they elude my full understanding. The one I am most attracted to is sonnet 73, which I find both exceedingly lovely and deeply resonant. I have opened this letter with the sonnet, and hope to traverse its deep beauties in what follows.

Miklós Radnóti

Miklós Radnóti was a Hungarian poet. (Born to Jewish parents, Radnóti converted to Catholicism.) He wrote poems celebrating love, affirmation, social criticism in the 1930’s. His poetry became more oppositional, although it retained his personal, lyric voice. The fascist government of Miklós Horthy saw him as an enemy, and imprisoned him in a forced labor camp. The war, as we now recognize, eventually went badly for the Axis forces, and in 1944 the inmates of the Yugoslav labor camp where Radnóti was incarcerated were forced into a long march ahead of advancing Russian troops.

Wallace Stevens: The Fierceness of Desire

Stevens is an odd poet for me to write about. A corporate executive – I dislike major corporations, and I dislike those who lead them – and in politics a conservative Republican – not my cup of tea – and a very cerebral poet (or seemingly so) – another direction that repels me: Wallace Stevens seems exactly the kind of voice I do not want to listen to. I know that if I were at a dinner, I would avoid talking to him, and to be truthful he would avoid talking to me, a leftist Jewish social critic.

And yet. And yet. He speaks important truths about important things. In my mind, always, is the opening and close of one of his best poems, “The Well-Dressed Man with a Beard:”

The Folly of Violence: Yehuda Amichai

Poems need not be long or difficult to impress themselves on us deeply.

Yehuda Amichai, an Israeli poet of surpassing brilliance, has written many poems which have left me speechless in admiration. One, in particular, is “The Diameter of the Bomb.” I don’t think it is particularly rich in difficulty or nuance. In fact, it is pretty simple. It elaborates on a geometric ratio. That’s it. But it packs an awesome punch.

Melville and Modern War

For twenty years I taught American poetry of the nineteenth century. The armature of the course was the poems of Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson, two writers who are arguably the greatest of all American poets. It increasingly struck me that Herman Melville, the celebrated author of the novel Moby-Dick, was the only other poet of that century who had a power and poetic vision that rivalled those two great contemporaries of his.

Gertrude Stein: An Astonishing Poetry

I don’t know where it was. Reading a newspaper? Listening to public radio? Skimming a book? Somehow, the phrase “all the” set a tiny anchor in my brain, and I thought, “I know that phrase. It is in a poem.” I searched the web but of course “all the…poem” did not yield what I was looking for. I thought, and then gave my efforts up. And then it hit me, welling up from some reservoir of memory. Gertrude Stein. Tender Buttons. And there it was.

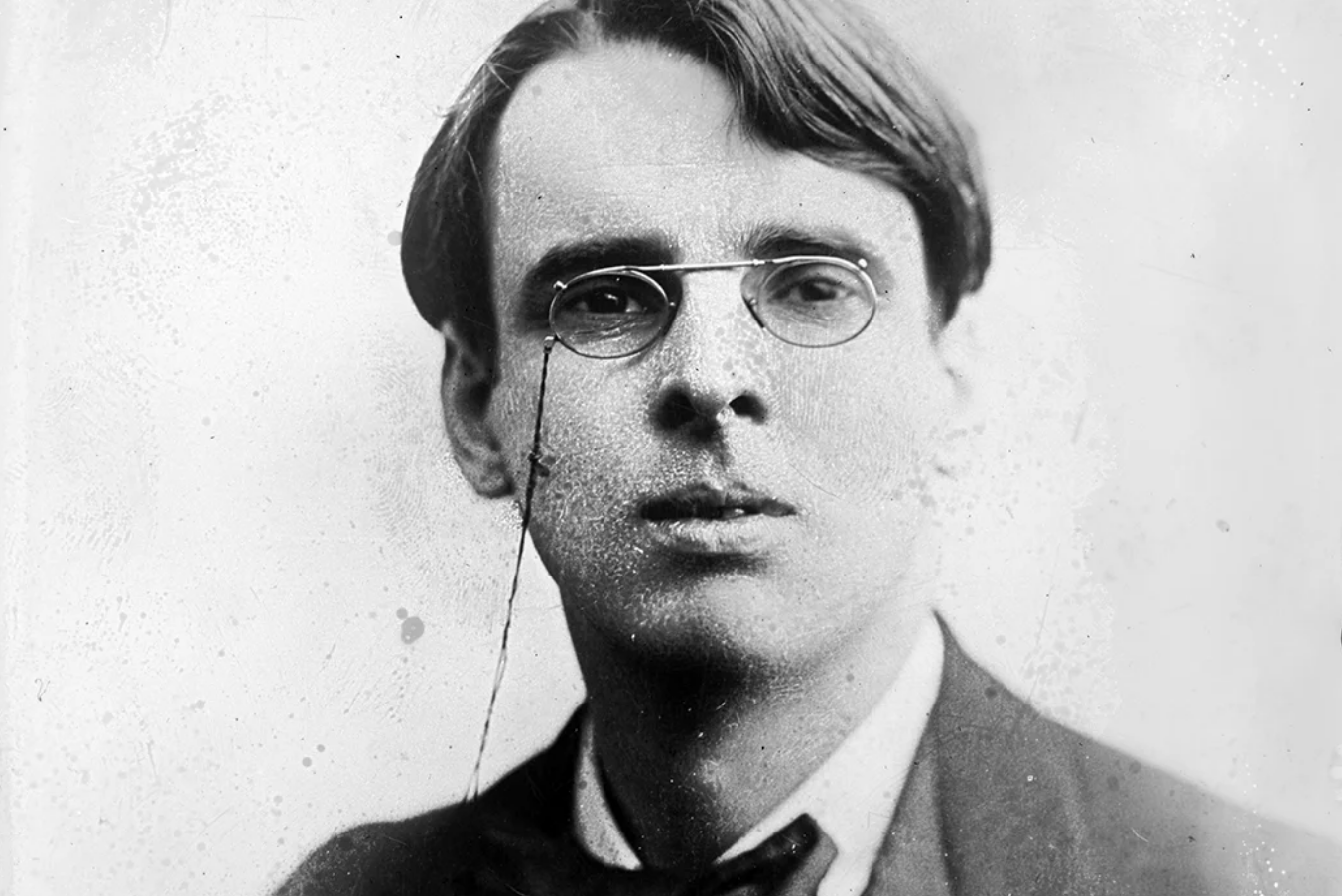

William Butler Yeats: The Rage Against Time

This poem is an example of the need to reread, and reread again, that I wrote of in my last letter. I came to this poem wanting to understand that, seen through the lens of time, all fades, that time is the destructive medium in which we live. I still think this is the ‘subject’ of this poem. But I have come to realize that this poem reshapes past time so that it is comfortable for the poet, and that this reshaping is, well, to use contemporary parlance, hegemonic: patriarchal, male-dominated, anti-progressive, and downright false.

Yeats: A ‘Perfect’ Poem

Thinking of writing a new letter, I pondered on whom to write about. With a sense of shock, I realized that I had not written extensively about William Butler Yeats, the greatest English-language poet of the twentieth century. Yes, yes, I know: “greatest” is not a term to be bandied about, especially since other poets were more dominant (Eliot) or more influential (Williams) or more ‘modern, (pick any of half a dozen). But he sure could write verse and, more, it sticks, sticks in the mind like no one else in relatively recent times

Frank O’Hara: Poet of the Present

Oh my. The start of this letter, a letter about a poem which is mostly ‘easy,’ is going to be sort of philosophical. Be prepared. But stick with me, because the poem is, well, easy. Easy and not easy. Both. Before I engage in philosophical musings, however, let me tell you the ‘foreground’ of the poem, which I am sure you recognize.

MARK DOTY “Atlantis: Part I, Faith”

A few days ago I went for a walk with a friend, and we talked about his dog, an Irish Setter. I said I knew a wonderful poem about a setter, and when I came home I looked it up. (I am not sure it is about a setter, but that is how I remembered it…) It is the final poem of a magnificent poetic sequence, “Atlantis,” written by Mark Doty as a meditation on and celebration of his partner Wally Roberts, who in 1989 tested positive for AIDS and subsequently died of that disease.

Two Poems by Sappho

It seems to me one of the wonders of our age. In 2004, examining the papier-mâché (known as cartonnnage) which wrapped an Egyptian mummy, scholars found sheet of papyrus that contained a ‘complete’ poem of Sappho. It is the earliest manuscript of a poem of Sappho.