A.E. Housman, “Terence, This is Stupid Stuff”

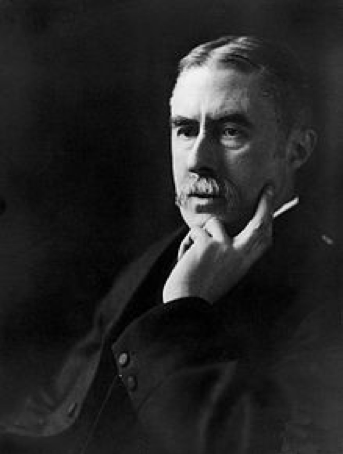

A. E. Housman, photo by E. O., Hoppe, 1910

I wrote an introduction to this poem, which follows:

Gerard Manley Hopkins in one of his late sonnets, addressed his writers’ block. (No, I have not had writer’s block). His concluding four lines are one of my favorite passages, lines I recite to myself often:

Sweet fire the sire of muse, my soul needs this;

I want the one rapture of an inspiration.

O then if in my lagging lines you miss

The roll, the rise, the carol, the creation,

My winter world, that scarcely breathes that bliss

Now, yields you, with some sighs, our explanation.

From Hopkins to Dickinson: When her literary correspondent Thomas Wentworth Higginson visited Emily in Amherst, Massachusetts they had what, in my view and perhaps in his, was (though enigmatic) one of the richest conversations in history. Among the other things she said, as Higginson wrote his wife summarizing their encounter, was this: "If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can ever warm me, I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only ways I know it. Is there any other way?"

I’m not Emily Dickinson, and my criterion for poems is not hers, though I find hers stunning. For me, it is what Hopkins describes: finding in a poem “the roll, the rise, the carol, the creation.” If in some fashion the roll and rise are not there, what I am reading is not a poem. If it is, then it is a poem. A simple yardstick, but I have found it wonderfully serviceable.

But I began with Hopkins not because of that marvelous line, but because of its last word, ‘explanation.’

I had intended, on leaving Washington in January, to return to sending out a poem a month. Instead, I embarked on a self-indulgent and happy project. Having read hundreds of mystery novels during my time working on Capitol Hill – my great escape from the pressures of dysfunctional government and from pushing a progressive agenda in the face of very strong headwinds – I decided to write one. So rather than write about poems, I spent day after day happily spinning out a story of murder and the search for the murderer . . .[1]

And then September came, and I returned to teaching. Courses in poetry. A wonderful pleasure.

But as my introduction to poetry course turned to Emily Dickinson I could feel some of my students thinking – without articulating it – ‘oh, some of these poems are so depressing. She confronts such despair. I’m not sure I like these poems.”

As it happens, last week a friend told me of a visit to the doctor – a most enlightened doctor, I think – who suggested an occasional evening beer as a way to modestly alleviate anxiety. Almost without thinking, I citedto her a couplet by A. E. Housman: “For malt does more than Milton can/ To justify God's ways to man.” (Turns out, my recollection of the first word was wrong. Oh well.) My friend had never read Housman, so I looked up the poem, thinking to send it to her.

And was wonderfully surprised by how directly it addressed what I feared some of my students might be thinking about Emily Dickinson. I read the poem again, and immediately sent it to my friend. Then I gave copies to three of my colleagues. What a wonderful poem, I thought.

And so I send it to you. It is fairly long, but I think you will love it as much as I do. At least, I hope so. And it is not a heavy slog: it makes for, dare I say it, delightful reading.

Yes, you will come to a ‘serious’ side of this poem, but it is fun to read. No poem I have sent out, except Mayakovsky’s “An Extraordinary Adventure,” has the good humor and spirit with which this begins. It is a good thing, sometimes, not to take oneself too seriously. The same goes for poems . . . even though the poem will finally, say the opposite of what I have written in the first part of this sentence.

Terence, This is Stupid Stuff

A.E. HOUSMAN (1896)

"Terence, this is stupid stuff!

You eat your victuals fast enough;

There can't be much amiss, 'tis clear,

To see the rate you drink your beer.

But oh, good Lord, the verse you make,

It gives a chap the belly-ache!

The cow, the old cow, she is dead;

It sleeps well, the horned head...

We poor lads, 'tis our turn now

To hear such tunes as killed the cow!

Pretty friendship 'tis to rhyme

Your friends to death before their time

Moping melancholy mad!

Come, pipe a tune to dance to, lad!"

Why, if 'tis dancing you would be,

There's brisker pipes than poetry.

Say, for what were hop-yards meant,

Or why was Burton built on Trent?

Oh many a peer of England brews

Livelier liquor than the Muse,

And malt does more than Milton can

To justify God's ways to man.

Ale, man, ale's the stuff to drink

For fellows whom it hurts to think:

Look into the pewter pot

To see the world as the world's not.

And faith, 'tis pleasant till 'tis past:

The mischief is that 'twill not last.

Oh I have been to Ludlow fair

And left my necktie God knows where,

And carried half way home, or near,

Pints and quarts of Ludlow beer:

Then the world seemed none so bad,

And I myself a sterling lad;

And down in lovely muck I've lain,

Happy till I woke again.

Then I saw the morning sky:

Heigho, the tale was all a lie;

The world, it was the old world yet,

I was I, my things were wet,

And nothing now remained to do

But begin the game anew.

Therefore, since the world has still

Much good, but much less good than ill,

And while the sun and moon endure

Luck's a chance, but trouble's sure,

I'd face it as a wise man would,

And train for ill and not for good.

'Tis true, the stuff I bring for sale

Is not so brisk a brew as ale:

Out of a stem that scored the hand

I wrung it in a weary land.

But take it: if the smack is sour,

The better for the embittered hour;

It should do good to heart and head

When your soul is in my soul's stead;

And I will friend you, if I may,

In the dark and cloudy day.

There was a king reigned in the East:

There, when kings will sit to feast,

They get their fill before they think

With poisoned meat and poisoned drink.

He gathered all the springs to birth

From the many-venomed earth;

First a little, thence to more,

He sampled all her killing store;

And easy, smiling, seasoned sound,

Sate the king when healths went round.

They put arsenic in his meat

And stared aghast to watch him eat;

They poured strychnine in his cup

And shook to see him drink it up:

They shook, they stared as white's their shirt:

Them it was their poison hurt.

--I tell the tale that I heard told.

Mithridates, he died old.

A.E. Housman taught classics at University College, London. His first and greatest book, A Shropshire Lad, was published in 1896. Scholars look back on it as a fine book in a dying tradition – modernism in painting, music and poetry was about to be born into the world – by a minor poet.

Hardly. Housman wrote in a throwback style using rhyme, meter and restraint in a time when poetic language, rhythm and form were about to be revolutionized, but that does not mean, to me at least, that he can’t speak powerfully or that in his lines I cannot find “the roll, the rise, the carol, the creation.” Of all the poems I know, I probably recite to myself, as I move through my life and my world, his “Loveliest of trees the cherry now” more than any[2]. It speaks to me, deeply, even though it is rhymed and not elliptical, even though it tells more than it shows, even though it eschews ambiguity and obscure symbolism and all that other good modern stuff.

To my mind, Hopkins is either a great minor poet, or a wonderful but lesser major poet. Why the modest reservations? I think his canvas and his palette are maybe not broad enough. What he does, he does remarkably well, but then: does he do enough things?

I promised you would like “Terence, This is Stupid Stuff” and you have probably found that to be the case. If not, bear with me.

One of the hardest parts of the poem is the opening, and that is because we are accustomed to most non-narrative, non-dramatic, non-epic poems being about the poet. In the first stanza, which we notice in quotation marks, it is not Housman speaking, but some fellows in a bar, and they are not speaking to Housman but to some guy named ‘Terence.’

"Terence, this is stupid stuff!

You eat your victuals fast enough;

There can't be much amiss, 'tis clear,

To see the rate you drink your beer.

The fellows are in a pub. They note how he drinks his beer: fast, and lots. A sunnier or less pompous beginning of a poem is hard to imagine. ‘Stupid stuff.’ And yet you eat your supper pretty damn fast. You guzzle your beer.

The “stupid stuff” is, as we will learn, his poems. “Oh, good Lord, the verse you make/It gives a chap the belly-ache!” And then the chaps mimic his poems, which in their unlettered but not unobservant way they understand speak of mortality and the long forgetfulness that is death. Terence is not drinking with literary critics, professors, or any sort of intellectuals, yet they understand the substance of his poems nonetheless, although they reduce it to the ridiculous.

The cow, the old cow, she is dead;

It sleeps well, the horned head...

Such is the stuff of poems to his companions in the pub and they feel afflicted when they hear such verses. A good friend, they insist, would sing “a tune to dance to” rather than a poem about death that will “rhyme/your friends to death before their time.”

Should I tell you the poem is in couplets, the predominant verse form of the eighteenth century and not used all that often afterwards and that his use of octameter -- eight syllables to the line – makes it sound a whole lot less serious than the pentameter used by such ‘greats’ as Shakespeare, Milton and Wordsworth? I guess I just told you, so let’s proceed to the second stanza, in which Terence responds.

The fun, and the lightness of the lines, continues. Terence reminds them that there is better dancing music than poems. If you want to prance around, there’s always beer…

Why, if 'tis dancing you would be,

There's brisker pipes than poetry.

Say, for what were hop-yards meant,

Or why was Burton built on Trent?

Hops, of course, is along with malt a key ingredient of beer. And Burton upon Trent? That is, in our day, what Wikipedia is for: “Burton upon Trent, also known as Burton-on-Trent or simply Burton, is a town straddling the River Trent in the east of Staffordshire, England. Burton is best known for its brewing heritage, having been home to over a dozen breweries in its heyday.”

Lots of noblemen brew better stuff than poets like Terence in his poems or the great poet John Milton does. The reference to Milton comes in the next couplet, with its allusion to the opening of Paradise Lost, in which Milton asserts that his aim is “to justify the ways of God to men.” As I wrote earlier, I love this line and quote it often – including the other day.

And malt does more than Milton can

To justify God's ways to man.

Nobody has ever, ever, come up with a more trenchant and telling attack on poetry than these two lines. If we want the universe to make sense, we’d be better off drinking than looking for answers in poems. Of course, as the poem proceeds, Housman will undermine these chaps he is talking to, argue against them, and build a stirring defense of poems.

But for now: “Ale, man, ale’s the stuff to drink.” (Of course, the claim destabilizes itself because it ends not with a period but a comma, and what follows is: “For fellows whom it hurts to think.”)

Ah, Terence says, look into your tankard and you can “see the world.” We pause just a beat, I think before the surprising second half of the line, “as the world’s not.” But while drinking makes the world pretty as one drinks, that prettiness is brief in compass. Time passes and drink wears off. “And faith ‘tis pleasant till ‘tis past/The mischief is it will not last.”

Hilarious, the example he gives of the pleasures of drink and the terrible psychological hangover after. It starts out as a comic film that requires a Buster Keaton or a Adam Sandler:

Oh I have been to Ludlow fair

And left my necktie God knows where,

And carried half way home, or near,

Pints and quarts of Ludlow beer:

Then the world seemed none so bad,

And I myself a sterling lad;

And down in lovely muck I've lain,

Happy till I woke again.

Then I saw the morning sky:

Losing his tie in a drunken stupor. The surge of exhilaration of being drunk. Pushing doubts at bay in an alcohol-based surge of energy. I love that lying down in the mud (“lovely muck”) and not caring, and the unstated shock of waking up in a muddy ditch…

But of course the alcohol-induced haze is just that, a haze. “Heigho, the tale was all a lie.” And then, amid all the bonhomie we have thus far encountered – “Ale man, ale…faith, ‘tis pleasant…pints and quarts of Ludlow beer…sterling lad…happy…heigho” comes a line as deep and trenchant as any line a poet has ever written, bringing us to what I might call reality or truth: “The world, it was the old world yet.” The bonhomie, or at least the lightness of the octosyllabic lines and the diction reasserts itself, banging home the truth but in the lightest of fashions:

The world, it was the old world yet,

I was I, my things were wet,

Of course his clothes are wet. He has, after all, lain down in the muck.

Then Housman states the great flaw in drink: it doesn’t last, and one has to get drunk all over again. “And nothing now remained to do/But begin the game anew.”

The third stanza draws a conclusion, obviously, because its first word is “therefore.” It begins with what happy drunks cannot acknowledge, including Terence’s drinking companions, “whom it hurts to think.” Life is often tough – more often that than fortunate – and we end up in decline and death[3]. The sprightly octosyllabic verse hides the truth at the same time as the poet reveals it:

Therefore, since the world has still

Much good, but much less good than ill,

And while the sun and moon endure

Luck's a chance, but trouble's sure

This being the case, wisdom would seem to lie in preparation for that trouble that is sure to come, “I'd face it as a wise man would,/ And train for ill and not for good.”

Therefore, the poem moves to conclude, it may make more sense to write poems about trouble than to sing songs of cheer or “a tune to dance to.” Poems do not have the consolatory power of beer, though they may have more value.

'Tis true, the stuff I bring for sale

Is not so brisk a brew as ale:

Out of a stem that scored the hand

I wrung it in a weary land.

But take it: if the smack is sour,

The better for the embittered hour;

It should do good to heart and head

When your soul is in my soul's stead;

And I will friend you, if I may,

In the dark and cloudy day.

That ‘stem that scored the hand?” The toughest line for me in this rather transparent poem. I think it means the pen he writes with and that the writing comes from/with laceration and not delight. His verse is “wrung” from him, and it comes from a place no one wants to vacation in or even visit, a “weary land.” The poem’s taste is” “sour,” but that taste is suitable for “the embittered hour.” Not beer, no, but a beverage suitable to “do good to heart and head.” Really, this sour drink? When a man or woman, say the reader of this poem, is in as dire straits as Terence sometimes discovers himself in, “when your soul is in my soul’s stead,” the brew may be worthy of drinking. The poet who writes this poem will be in those circumstances be our friend, and accompany us not to the pub or bar – we can find many friends there on our own – but on a “dark and cloudy day.”

The poem could end at this point, for the spectacle has concluded with this serious realization. But it doesn’t. If the poem begins in comic drama – the fellows in the pub making fun of the poet who writes verse they see as “The cow, the old cow, she is dead” –it ends in narrative. The final stanza tells a story about the mythic Mithridates, long-ago ruler of what today is Turkey.

In the first eight lines of the final stanza, the poet provides the setting for the story. Living in a treacherous land (analogous to us, who live existence where “trouble’s sure”). Mithridates knows there is a danger that he will be poisoned. In a story so widely told that many kids know it, he takes small and then increasingly larger portions of poison so that his body will grow accustomed to the toxins and be able to sustain any future ingestion without damage. (Kind of like vaccination, in our age.) Having “sampled all her killing store,” Mithridates can sit easy on his throne.

And easy, smiling, seasoned sound,

Sate the king when healths went round.

When conspiring nobles or enemies toast him with poisonous wine he, “seasoned,” can quaff the liquid that would otherwise kill him. What wonderful lines – you can see the enemies of the king respond, I think – follow:

They put arsenic in his meat

And stared aghast to watch him eat;

They poured strychnine in his cup

And shook to see him drink it up:

Ah, Mithridates knew. If you accommodate yourself to the dangers which face you, if you are inoculated, you will not die of what would otherwise destroy you. Not the king but his putative poisoners die from consuming the poisoned meat and drink

The final couplet shows Housman’s remarkable skill. It shocks me every time I read it. Not what it says, but how it says it. The first of those two lines is iambic, almost too conventional in its meter: “I hear [stress] the tale [stress] that I [stress] heard told [stress].” What follows is that mouthful, “Mithridates” is iambic but amazingly alien in this poem of silliness and lads and cows and ale and “my things were wet.”

And then. Well, a rarity in English verse is the spondee, two stressed syllables in one metrical foot[4]. What do we have here? Three stressed syllables in a row. “he [stress] died [stress] old [stress.]” Way beyond a spondee[5]. You could look it up. (I did.) In Greek and Roman verse, where feet were comprised of long and short syllables, rather than stressed ones, there was something known as molossus. (I told you, I had to look it up.) Three long syllables in a row. In English? Well, three stressed syllables in a row just doesn’t happen.

Except Housman does it at the conclusion of “Terence, This is Stupid Stuff.” “Mithridates, he died old.” Poems can help us through “the dark and cloudy day” that is always coming, can sustain us “in a weary land,” can “do good to heart and head.” Death will come, but we can, like Mithridates, grow old, forewarned and forearmed by what we read. Poetry can save your life.

Amazing, that Housman can start with beer and end with one of the deepest reasons to read poems. All in octosyllabic light verse. Ending with that – what was it called? – molossus.

What a poem. To me, a tour de force.

_________________

Here’s the wonderful Housman poem I promised. Not tough to read, but resonant nonetheless.

Loveliest of trees, the cherry now

Is hung with bloom along the bough,

And stands about the woodland ride

Wearing white for Eastertide.

Now, of my threescore years and ten,

Twenty will not come again,

And take from seventy springs a score,

It only leaves me fifty more.

And since to look at things in bloom

Fifty springs are little room,

About the woodlands I will go

To see the cherry hung with snow.

Footnotes

[1] No, the project is not done. I wrote the book, but I need to rewrite it as well. There is always work to look forward to, and I look forward to re-engaging my ‘detective.’

[2] I will append this wonderful poem at the end of this essay,.

[3] Oh how those early lines now seem ironic, making more sense than the chaps in the pub realize:

But oh, good Lord, the verse you make,

It gives a chap the belly-ache!

The cow, the old cow, she is dead;

It sleeps well, the horned head...

[4] A foot, a unit of the meter or rhythm, is almost always composed of stressed and unstressed syllables.

[5] A foot composed of two stressed syllables.