John Keats - “To Autumn”

I began this letter in the earlier days of fall, since Keats seemed to me to capture the season so wonderfully; I continued to write it as this year’s marvelous fall stretched out and out and out, so that now, in mid-November, yellow leaves are still on the trees in Vermont, the grass is bright green, and the skies are a blue that is a lighter shade of lapis lazuli. Maybe the flowers are mostly gone, the bees mostly departed from gathering pollen (although I saw two on two late dandelions, and a late-blooming chrysanthemum had a dozen), the apples picked or fallen from the trees. Yet this year’s miraculous autumn endured….

To Autumn

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run;

To bend with apples the moss'd cottage-trees,

And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells

With a sweet kernel; to set budding more,

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For summer has o'er-brimm'd their clammy cells.Who hath not seen thee oft amid thy store?

Sometimes whoever seeks abroad may find

Thee sitting careless on a granary floor,

Thy hair soft-lifted by the winnowing wind;

Or on a half-reap'd furrow sound asleep,

Drowsed with the fume of poppies, while thy hook

Spares the next swath and all its twined flowers:

And sometimes like a gleaner thou dost keep

Steady thy laden head across a brook;

Or by a cider-press, with patient look,

Thou watchest the last oozings, hours by hours.Where are the songs of Spring? Ay, where are they?

Think not of them, thou hast thy music too,--

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day,

And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue;

Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft

The redbreast whistles from a garden-croft,

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies.

It is fall here in Vermont. While many, spurred on by countless Chambers of Commerce, come here to see the leaves turn – and turn they do, in wonderful colors of orange and scarlet and yellow and brown – I think on other things. The warm sun, no longer hot, no longer lasting far into the evening, yet casting a mellow glow on everything. The blue skies, which will too soon be chased away by winter’s grey. The late flowers blooming in our garden, attracting bees and bumblebees, wasps, and the occasional monarch butterfly. This is, as Keats proclaims, a “season of … mellow fruitfulness.”

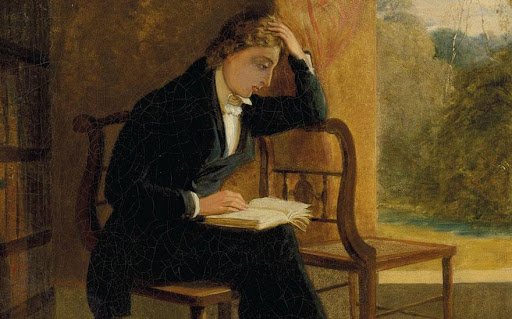

Is Keats’s “To Autumn” the most beautiful poem in the English language? I often think so. And unlike some of my best friends, I do not on the whole love Keats, do not admire him as the apotheosis of the poet. He is a great poet, for sure, but maybe a little to perfect for me. Call me cold-blooded – I actually think Keats is that, so often clean and perfect, even as he is divided and ambivalent – but I prefer Wordsworth, even though he wrote in what was, assuredly, what Keats claimed of him in a letter, the “egotistical sublime.” In the other great odes Keats did in fact write of himself, and of conflicts within himself; in “To Autumn” the self has disappeared into the world about the poet, the conflicts are melded into a harmony of what is, the whole poem a merging of what is and what shall be.

I believe no more lovely poem has ever been written than “To Autumn.” It praises the turning season before that season goes away. It also meditates, I think, on the glories of living in a world where human existence always gets swallowed up by death. We do not go on and on; our ending is certain, inscribed in our genes and in the way of all things. Yet, as Theodore Roethke said in a love poem I wrote you about (“I Knew a Woman”), “what prodigious mowing we did make.” There is a richness to our lives – “There lives the dearest freshness deep down things,” Gerard Manley Hopkins wrote in a great sonnet – that we need to be reminded of even as we acknowledge that death, an ending, lies ahead for all of us.

Let’s start, in this lovingly mellifluous poem, with the stanzas. Largely iambic (an unstressed or shorter syllable followed by a stressed or longer syllable) it is nonetheless remarkably varied. [I think the first line starts with a trochee before settling into iambs, the stress falling on SEAson in line one, while line two begins with a spondee (two stresses) in CLOSE BOSom which is balanced by a pyrrhic foot (two unstressed syllable) later in the line, OF THE. Hmm. Like almost all great verse, which depends on regularity for an underlying sense of order, while at the same time providing variation so that the order does not become boring, mechanical or stifling, Keats augments his iambic meter with variations. From the start.]

So we are reading a poem that is roughly in iambic line, which itself is unsurprising because it is thought that iambs come closest to reproducing the speech patterns of spoken English, and because our greatest wordsmith, Shakespeare, wrote (predominately) in iambic pentameter.

On to the rhyme scheme, which as you will see is close to regular, but not entirely so. Here are the rhymes of the three stanzas:

ABAB CDE DCCE

ABAB CDE CDDE

ABAB CDE CDDE

As revealed above, the line endings (unconnected to one another) of lines 5-7 provide the rhymes of lines 8-11, but not in exactly the same order in each stanza. As with the meter, regularity (so that we feel an order to the lines), but not entirely so (so that we sense that music and not mechanism rules). Oh, that Keats. As far as I know, the eleven-line stanza is something he made up specifically for this poem.

Before we look at the poem closely, let me point out two ‘progressions’ in the three stanzas. Keep them in mind as you read through the poem. Of the three stanzas, the first is about morning, the second, about afternoon, the third, about evening, or what the British in older days lovingly called the ‘gloaming:’ The dusk. Also, the first stanza focuses on tactile things, the second on sight (on seeing things), the third on hearing (the “music” of the ending of day). As long as we are on the differentiation of stanzas: we move from fruitfulness in stanza one, to labor and “careless’ drowsiness in stanza two, to decline and “soft-dying” in stanza three.

So that first line. Whew. The whole poem is there, “Season…of mellow fruitfulness.”

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run;

To bend with apples the moss'd cottage-trees,

And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells

With a sweet kernel; to set budding more,

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For summer has o'er-brimm'd their clammy cells.

Fall is a time of mellowness, when fruits (grapes, apples) reach maturity. But I think of that first line again and over again, the “mellow fruitfulness” that speaks to me of calm and richness, traits that mark those lovely September and October days. The sun is declining, as is the year (shorter days, less warmth, leaves to be shed), yet there is a mellowness to it all. I could not say it better, and in fact do not wish to: “Season of mellow fruitfulness.” [Yesterday my wife and I and some friends drove across Vermont to a country home located on a small mountaintop, views upon views, leaves turning yellow and scarlet everywhere: And along our drive, and when we got to the mountaintop, we saw low-hanging mists that arose from the valleys, the residue of warm streams sending aloft humid plumes to meet the cooler air…] “Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness.”

Of course the autumn is the “close bosom-friend of the maturing sun.” The sun, in decline as the earth turns on its axis, is partner to the declining season. (Before I go on, let me highlight that word, “bosom.” I spoke the first line of this poem to a friend last night, and she repeated back to me the second. I was struck, hearing it aloud, with the word “bosom.” Yes, Keats has it exactly right: The bosom here is not so much sexual as nurturant, a bodily part one associates with suckling, with feeding. As, in the rest of the stanza, the fruitfulness of the world – apples, grapes, nuts, squash – comes to maturation and feeds us, makes us aware of how hospitable this life we are born into can be.)

Keats is quick to offset that decline of the “maturing sun” by “fruitfulness;” the maturing sun ‘conspires’ with the vines to produce a rich harvest of grapes. The season may be diminishing in terms of light and warmth, but there is a richness that is a hallmark of the season, a plethora of ripe fruits: Not just grapes, but apples, late summer squashes in the garden, nuts in their shells. Nowhere has anyone, anyone, more clearly revealed that as endings (death?) appear on the distant horizon (‘ 'tis like the Distance/On the look of Death” wrote Emily Dickinson, in a very great poem about the declining sun in the days of late autumn and early winter), there is a concurrent ripeness that suffuses everything.

The lines cascade onward in that first stanza. Not only are fruits and nuts (that “sweet kernel”) ripening, but late flowers bloom. It is a marvel to me, a real marvel, to see how many bees the late flowers in my garden attract. In our backyard garden, they buzz around and into late small yellow blooms on arugula past its leafy prime, into obedient plants with their spikes of pink-purple flowers, into caryopteris bushing out with small blue flowers. The bees flock to all, entering into each flower to extract pollen. Along country roads and at the margins of meadows, goldenrod and small purple asters attract scores of bees. Of course those buzzing insects believe, with Keats, that “warm days will never cease.” That tough final line, “For summer has o’er-brimmed their clammy cells”? Because summer has been so fruitful, the damp cells of the bees, their honeycombs – honey-filled – are brimming over with “mellow fruitfulness.” Honey abounds, as do apples and nuts and grapes. (I don’t like the line – hey, I guess no poem is ‘perfect’ – because “clammy” doesn’t work for me. So a small blemish on what is otherwise a glorious, glorious poem.)

Before we move onward to the second and third stanzas, let us linger on that wonderful first stanza. In that stanza, and in that remarkable first line (“mellow fruitfulness”) are the entire poem, fruitfulness and ripeness and sweetness laid against the season of endings. Are we making too much of this to suggest that life’s richness flourishes even as we move toward death? (Biographical: Keats wrote his five other ‘great odes’ in the spring of 1819. He wrote this one on a single day in the autumn of 1819. It was the last of his poems: The struggle for money, and the advancing tuberculosis that would lead to his death in early 1821, precluded his writing more poems. So perhaps one does not go too far in suggesting that in this last, great poem Keats is meditating on his own coming death, not just the ending of the seasons of the year. He had been attending, caring for, his tubercular brother Tom since the start of 1818; Tom died on December 1, 1818. Keats himself would die, of tuberculosis, in early 1821.) Stanza one is shaped, overall, by the “season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,” autumn; its subject is the remarkable fruitfulness one encounters as the year nears its ending, as the sun is “maturing,” as observers “think warm days will never cease.” Endings approach, yet the season glows with life and its richness. Death and endings are finely balanced against the richness of existence. As Lear says of death, perhaps “Ripeness is all.”

Fruitfulness and the declining sun are “close bosom-friend[s].” I suppose that is easy to say in a poem, since words come easily to many. But Keats himself was feeling the heavy weight of life: Wordsworth, whom he both revered and argued against, wrote of this burdensome weight that grinds us down,

Full soon thy soul shall have her earthly freight,

And custom lie upon thee with a weight

Heavy as frost, and deep almost as life!

Wordsworth wrote this in an earlier ode (1804) than those of Keats. The business of life, and the foreknowledge of death – his own brother having died, and the intimation that he, John Keats, was not long for the world – are part of the subtext of the poem we are considering. Autumn is a season of mellow fruitfulness, but it is also the season which leads us into winter, the culmination of the annual cycle, when the organic world either dies or simulates dying in a long sleep.

It is hard to leave this first stanza behind, all the “mellow fruitfulness.” Only the (mistaken) thinking of the bees, that somehow “warm days will never cease,” hints at the closure that is to come, hints that fruitfulness is not an everlasting condition. What a case, though, that Keats makes for the wonders of the world, even as it approaches a kind of ending! Again and again, as I wandered this year through the days of an extended and wondrous fall, I thought of Keats, and how he understood how marvelous the autumn is, how peaceful, calm and rich.

Who hath not seen thee oft amid thy store?

Sometimes whoever seeks abroad may find

Thee sitting careless on a granary floor,

Thy hair soft-lifted by the winnowing wind;

Or on a half-reap'd furrow sound asleep,

Drowsed with the fume of poppies, while thy hook

Spares the next swath and all its twined flowers:

And sometimes like a gleaner thou dost keep

Steady thy laden head across a brook;

Or by a cider-press, with patient look,

Thou watchest the last oozings, hours by hours.

The second stanza begins with a personification of autumn, as if Keats is seeing a mythical figure (Autumn) seated on a barn floor, dozing as the mellow day itself dozes in the light of the “maturing sun.” The richness of autumn is “careless,” without care – not focused on the impending winter that is to come; also “careless’ in the profligacy with which she dispenses the rich fruitfulness of the season, to all who seek fruitfulness and even to those who do not seek it but find it nonetheless. The wind of the fourth line emphasizes that carelessness, lifting the personified Autumn’s hair without plan or purpose, lifting it “soft”ly as it also winnows the grain, separating fruitful seed from chaff.

After seeing her in a granary, where the kernels harvested in fall are winnowed and stored, Keats imagines Autumn “sound asleep” on a furrow in a field, the grain “half-reap’d” for that winnowing that has transpired in the previous line. There it is, although we only half-see it: Rich grain, but it is “reap’d” and winnowed, harvested. Death is here, but part of a nurturant process, as necessary to ongoing life as the rain of summer was. No wonder Keats was, as in an earlier ode, “half in love with easeful Death.” Here, death, endings, are indeed “easeful.”

Keats suggests the opium eater’s soft delirium, a sleep that is mellow and fruitful: “Drowsed with the fume of poppies.” Here, in the sixth and seventh lines of the stanza, Autumn dozes in opiate-haze, yet her “hook/Spares the next swath and all its twined flowers.” Flowers bloom, diminished since many have been casualties of the harvest, of the advancing season. They are blossoming despite the fate that awaits them (further harvesting), just as the fruit and nuts of the first stanza ripen even as the year approaches its end. Once again, flowering, even as death approaches.

More harvesting, for now once again Autumn is personified, here “like a gleaner” who, with “steady head” laden with fruitfulness, proceeds “across a brook.” The image is of the late harvester carrying a load of rich harvesting across a small stream, symbol of the passage of time and perhaps of the boundary between – what? – life and fruitfulness, and death and peaceful sleep?

One last image of the personification remains. Here, in the final couplet of the stanza, Autumn waits “with patient look” as time passes, “hours by hours,” while the “last oozings” of fruitfulness are pressed out, harvested. The apples of the first stanza, “to bend with apples…And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core,” have been picked, sorted, stored, and what remains is taken to the cider press to be squeezed into cider. The fruitfulness of the first line is now stored for sustenance in winter.

In stanza one we encountered Autumn’s “mellow fruitfulness;’ in stanza two that fruitfulness in winnowed, reaped, gleaned and pressed out. The fruitfulness remains, but not in the fields: It will nourish us in days to come.

Could anything be better than what Keats has given us? Yes, for the last stanza, miraculous, is yet to come.

Where are the songs of Spring? Ay, where are they?

Think not of them, thou hast thy music too,--

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day,

And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue;

Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft

The redbreast whistles from a garden-croft,

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies.

The stanza begins with a repetition of “where are,” ”Where are the songs of Spring?, Ay, where are they?” Something is gone, lost, that season of youthful hope and exuberance, when the year is young, the trees budding. Now what remains are “stubble-plains,” the fruitful fields mown down to closely shorn stems. The harvest of mellow fruitfulness has ensued, yet autumn “hast thy music too,” and the poem counsels us to think of this music, and not of the songs of Spring which have been lost as time passes on.

There are bars, too, as in the bars of a prison – “barred clouds” – which preclude going back to the hopes of spring or the rich growingness of summer, yet the light still “blooms” through those clouds, even as the day sinks into evening, “soft-dying.” Autumn, which we recall is a “season…of mellow fruitfulness,” is not dark but suffused with a “rosy hue.” Even as the light declines, it colors the late season with a lovely glow. Bars there may be, but there is a wondrous color: There is late light, also, even as the seasons and the day decline.

Then come the lines that strike me the most strongly of any in the poem. Randall Jarrell once said of some lines from Walt Whitman, lines I think I have quoted before but which burn with a fierce flame in my memory:

In the last lines of this quotation Whitman has reached – as great writers always reach -- a point at which criticism seems not only unnecessary but absurd: these lines are so good that even admiration feels like insolence, and one is ashamed of anything that one can find to say about them.

Here are the lines, although I think I shall say something about them, even as they deserve the reverence that Jarrell points toward:

Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

The first half of the phrase, the “small gnats” mourning (mourning the loss of day, the loss of summer’s long light) along the willows that grow by the riverside, is lovely; but then Keats reaches the apex of poetry with his “borne aloft/Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies.” One thinks of how sensory this line is, attuned to the smallest of insects as they rise and fall with the autumn breezes, together, as we say, ‘in concert’ meaning both to come together and to make music.

This line, comprised of both sight (“borne aloft/or sinking”) and sound (“wailful choir”) and tactile sense (the “light wind” living and dying), is of the almost-stillness of the twilight of the season, where all is poised between… well, between not only day and night, but between life and death. Those almost insubstantial insects – gnats, midges -- rise and fall as the wind “lives or dies.” Poised on the margin of the day and the season, the insects show how little difference there is between life and death. They can rise, or they can fall.

Who has not seen these flights of insects by the margins of water, almost insubstantial as I just said, rising and falling? In them, Keats has found a memorable image (aural as well as visual and tactile) for the insubstantial – as he sees it, in this poem – boundary between life and death. Let me repeat what King Lear said, mad on the heath and yet seeing with a clarity that we too often lack, “Ripeness is all.” When what is fruitful, and we think of the first stanza, reaches the culmination of fruitedness, it falls from the tree. “Ripeness is all.”

[Forgive me, for I know I write too much of Walt Whitman, but here are the stunning lines which come late in “Song of Myself,” which Keats anticipates:

And as to you Death, and you bitter hug of mortality, it is idle to try to alarm me.

To his work without flinching the accoucheur comes,

I see the elder-hand pressing receiving supporting,

I recline by the sills of the exquisite flexible doors,

And mark the outlet, and mark the relief and escape.

Whitman tells us that we come into the world through the “exquisite flexible doors” of our mothers’ birth canal, and we leave it, “relief and escape,” in similar fashion, between the “exquisite flexible doors” which mark our “outlet” from life into death.]

The youth of spring has issued in maturity. The lambs born in March have turned into sheep, “full-grown lambs,” which “bleat” into this autumn landscape. Together with those insects and the coming “crickets” and “redbreast” and “swallows” they make the autumnal music he is hearing. One thinks of Wordsworth’s “Tintern Abbey”, where he describes “hearing oftentimes/ The still, sad music of humanity,/ Nor harsh nor grating.” This music is not harsh, nor is it grating. But Keats is not Wordsworth, here: He understands that the music is the music of natural cycles, something larger and greater than the suffering of humankind.

The poem ends with the music of autumn. “Hedge crickets sing.” “ Robins “whistle from a garden croft.” Swallows “twitter in the skies.” These sensory perceptions – and they are sensory! – exemplify what the stanza’s second line proclaimed of autumn, “thou has thy music too.” What a lovely quintet, those “mourning” gnats, lambs bleating loudly, crickets singing, the soft treble of robins whistling, the swallows twittering as they circle aloft.

It is a song of mourning, as the lines about the small gnats indicate. As the day softly dies, (“soft-dying day”) the swallows gather in the dusk and sing along with the diminishing light.

Keats, as I indicated at the start, had been tending to his dying brother, and in his own cough he must have recognized that the family illness, tuberculosis, which had claimed his brother Tom was also gathering within him. It takes courage, I think, to recognize that death and endings have their own beauty, that dying has a music too – a music as harmonious as the music of life – even though we mostly rail against death and are frightened of sinking into non-existence. Let me remind you that Keats nursed his brother through Tom’s final illness, so ‘death’ was not something abstract to him: It was concrete, material, real.

I actually do not know how to write about these final lines and their lovely music. One can understand why so many critics have found this the greatest of all English poems. In an earlier letter, I meditated on lines from Theodore Roethke that I find memorable, even though I do not know what they mean. Perhaps he was thinking about Keats, about the ending of this poem?

Nor can imagination do it all

In this last place of light: he dares to live

Who stops being a bird, yet beats his wings

Against the immense immeasurable emptiness of things.

Those swallows are beating their wings in the darkening sky. The music they make, that song that Keats is singing to us, is about dying, and how it is part of the great epic of living, not so much an ending as a merging with the cosmos.

Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft

The redbreast whistles from a garden-croft,

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies.

I think Randolph Jarrell got it right. Sometimes the words we utter to explain poems are irrelevant, and “criticism seems not only unnecessary but absurd: these lines are so good that even admiration feels like insolence, and one is ashamed of anything that one can find to say about them.” I myself read these final lines and grow silent. Fall “hast thy music too.” And what beautiful music, as Keats presents it to us in these closing lines, it is.