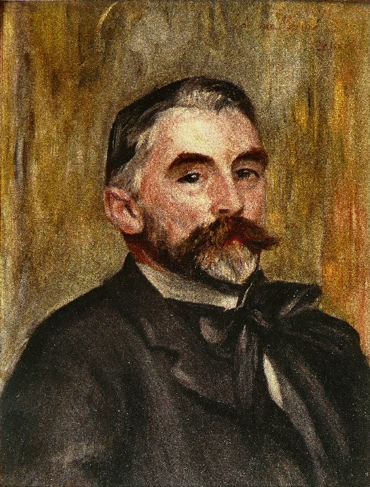

Mallarme and Yeats, “La Chair est triste” and “The Circus Animals’ Desertion”

Stéphane Mallarmé (painting by Pierre-Auguste Renoir)

William Butler Yeats

Every summer I envelop myself in chamber music at the Lake Champlain Chamber Music Festival One of the performances this past summer there was a piece for piano and violin by Claude Debussy. I don’t like Debussy, although I recognize that his easy movement away from tonality was a major progenitor of music in the twentieth century. Afterwards, I had a long conversation with my friend Mark Kessler about Debussy’s “L’apres midi d’une faune,’ which is based on a poem by Stéphane Mallarmé. So I read the poem. Yuk. Dreamy and, worse, a bit of a rape fantasy – or so it seemed to me.

This letter followed up on themes I touched on in my letter about du Bellay and Baudelaire.

He’s tough, Mallarmé, about as tough as poets get. I recently re-read a lot of his poems, and fell back on one I have loved for a long time only because its first line is so remarkable, and for a literature teacher, transgressive. Here’s the poem, “Brise Marine,” in my translation, which as usual does not capture the rhymes but does attempt to capture some of the rhythms of the poem. For the French original, see here.

Sea Breeze

The flesh is weak, alas, and I have read all the books!

To flee! To flee far off! I sense that the birds are drunk

From existing between the unknown spume and the skies!

Nothing, not even old gardens reflected in the eyes,

Can restrain the sea-drenched heart,

O nights! Not the desert clarity of my lamp

On the blank paper whose whiteness confronts the pen,

And not the young woman suckling her child.

I will leave! Steamer with swaying mast,

Weigh anchor for exotic coasts.A boredom, made desolate by the cruelty of hope,

Still believes in the great farewell of waving handkerchiefs!

And, perhaps, the masts inviting storms

Which may arise from a wind which formerly beat down the hulls

Of shipwrecks, mast-less, mast-less, without even a distant isle…

But, oh my heart, hear the song of the sailors!

So: Why this letter after I have discussed du Bellay and Baudelaire?

I think you can see how Mallarmé is channeling Baudelaire. He even copies Baudelaire’s words – “Lève l’ancre,” ‘Weigh anchor’ – to signify setting out on a voyage, almost the same words as are found in in the last section “Le Voyage,” “Levons l’ancre,” ‘let us weigh anchor.’ More important, he says that we dream of voyages away from ‘ennui.” Boredom. That most Baudelairean of words.

Ok, let’s look at that first line which I find resonates so cuttingly. “The flesh is weak, alas, and I have read all the books.” So much learned, and so little to show for it. We strive for learning, but as the line so terribly reminds us, learning is not worth much. (Yeats, whom I will consider next, agrees.) There is nothing in civilization that will save the poet, or the reader, and so both must embark on a journey to . . . something better, or something else. Terror: all our books, all our learning, and we still live in the sadness of our mortal bodies. Only, as we shall see later in the poem, only boredom is to be found in this emptiness. No wonder he wants, needs, to flee.

To flee! To flee far off! I sense that the birds are drunk

From existing between the unknown spume and the skies!

Off to the sea Mallarmé will go, channeling (as I said) Baudelaire. Nothing but travelling to far-off places can save him from his unhappy situation, from the horrible boredom which he will set before us at the start of the sestet. Most of the octet consists of a series of negatives: “Nothing…not…not…”

Nothing, not even old gardens reflected in the eyes,

Can restrain the sea-drenched heart,

O nights! Not the desert clarity of my lamp

On the blank paper whose whiteness confronts the pen,

And not the young woman suckling her child.

We long for the sea with our “sea-drenched heart” since the land will not suffice. (Quite the opposite of du Bellay, here, the Renaissance poet who longed for his native land with its hills and slate roofs and land breezes.) Already charmed by the sirens of the sea, gardens have no hold on Mallarmé, nor the paper (he is a poet!) which lies blankly before him, nor the fecundity of motherhood and the potential of infancy. He must leave. He will leave.

I will leave! Steamer with swaying mast,

Weigh anchor for exotic coasts.

I confess that these lines trouble me. I may be a dull reader, or Mallarmé may be an uninformed writer. What characterizes steamships is that they cross the waters under steam power, not wind power. They have boiler rooms, not sails. Oh well. He, the poet’s persona, sets off for distant and exotic coasts.

And now the sestet. What drives him, he who has read all the books and whose flesh is sad, is boredom. He had hoped for so much more. And he now has hopes of the voyage:

A boredom, made desolate by the cruelty of hope,

Still believes in the great farewell of waving handkerchiefs!

But the “cruelty of hope” is here too. That voyage to exotic coasts is itself a hope, one we desperately believe in. The sentimentality of the image, those on shore waving their handkerchiefs as the boat steams out of the harbor, should alert the reader if not the traveler that the voyage itself is a cruel hope, something destined to despair.

And, perhaps, the masts inviting storms

Which may arise from a wind which formerly beat down the hulls

Of shipwrecks, mast-less, mast-less, without even a distant isle…

“Perhaps” the masts of the embarking vessel will support sails filling with a wind that will propel the ship to exotic shores. Perhaps. More likely, the poem tells us, the winds will beat the boat into submission, snap the mast, condemn the passengers and sailors to shipwreck, to loss, to sinking in the immense blue sea. Emily Dickinson, writing at about the same time as Mallarmé, knew shipwreck well, although she lived inland. For her it was the emblem of inner loss.

A great Hope fell

You heard no noise

The Ruin was within

Oh cunning wreck that told no tale

And let no Witness in

The mind was built for mighty Freight

For dread occasion planned

How often foundering at Sea

Ostensibly, on Land

She ends another with an image that calls to mind the lines of Mallarmé we are considering. “It was not Death,” she begins as she considers that poem in the depth of despair, and she ends with this astonishing quatrain:

But most like chaos, -- stopless, cool,

Without a chance or spar, --

Or even a report of land

To justify despair.

Despair is, as Dickinson tells us, an endless shipwreck without hope of rescue.

And so back to Mallarmé, who after an image of being lost at sea without “even a report of land/ To justify despair,” ends his poem with the hopefulness of sailors, and the reader, and the poet:

Of shipwrecks, mast-less, mast-less, without even a distant isle…

But, oh my heart, hear the song of the sailors!

If Baudelaire had hopes for a voyage, Mallarmé does not. He still longs for the voyage, but knows it is doomed to shipwreck and loss. Mallarmé knows that the emptiness he has emphasized in the octet, an emptiness the voyager is fleeing at the end of that stanza and in stanza two, will reclaim the voyager in the end, Still, the sailors voyage onward, drawn by the need to find something new.

How different is William Butler Yeats in his final years! Earlier, he himself had thought of voyaging. “Sailing to Byzantium” is one of the most perfect poems in English, a masterpiece, a tour de force. It’s all about an older man (Yeats is actually middle aged) who finds the youth and sex of Ireland discomfiting, and so wishes to ‘sail the sea’ to a mythical past place where all was beauty and harmony. [Baudelaire also longed for this place, as he reveals in famous and beautiful lines: “Là, tout n'est qu'ordre et beauté,/ Luxe, calme et volupté.” In Richard Wilbur’s brilliant translation: “There, there is nothing else but grace and measure,/ Richness, quietness, and pleasure.” Mallarmé longed for it, always…]

Yet at the very end of “Sailing to Byzantium,” is a very great irony, for the ‘art object’ Yeats celebrates is a copy of something from the very nature he has been fleeing, a bird. And that ‘mechanical bird,’ however richly designed, is revealed in the old fairy tale to lack the faithfulness and beauty of a real, actual, nightingale.

Ah, but I digress. For what I tried to say was that the younger Yeats, and the middle-aged Yeats, wanted to voyage, to escape from this world of the real and the everyday. (I hasten to add that Yeats knew such escape was a chimera, and his poems of escape are always deeply ironic, from his early Celtic Twilight poems to the great poems of his maturity. Smart man that Yeats, even if he was love-besotted and a believer in Gurdjieff’s spirit world.)

But now we are considering late Yeats. “The Circus Animals’ Desertion” is a poem whose first section addresses his writer’s block: fancy words and images will no longer come to him. Then comes a second, longer, section, which examines the poet’s great accomplishments. This second section considers his own work as a dramatist. These are extraordinary verses, but not great as great as what follows them, and so will not discuss them. You need not have read the dramas to understand the ‘point,’ which is that having written ‘fancy’ stuff in the past does not suffice as he faces his age and his mortality.

And then the final section, which is as good a poetry gets. One of the high points of human creativity, even as it considers a ‘low’ point. Here is the whole poem, “The Circus Animals’ Desertion.”

I

I sought a theme and sought for it in vain,

I sought it daily for six weeks or so.

Maybe at last being but a broken man

I must be satisfied with my heart, althoughWinter and summer till old age began

My circus animals were all on show,

Those stilted boys, that burnished chariot,

Lion and woman and the Lord knows what.II

What can I but enumerate old themes,

First that sea-rider Oisin led by the nose

Through three enchanted islands, allegorical dreams,

Vain gaiety, vain battle, vain repose,

Themes of the embittered heart, or so it seems,

That might adorn old songs or courtly shows;

But what cared I that set him on to ride,

I, starved for the bosom of his fairy bride.And then a counter-truth filled out its play,

‘The Countess Cathleen’ was the name I gave it,

She, pity-crazed, had given her soul away

But masterful Heaven had intervened to save it.

I thought my dear must her own soul destroy

So did fanaticism and hate enslave it,

And this brought forth a dream and soon enough

This dream itself had all my thought and love.And when the Fool and Blind Man stole the bread

Cuchulain fought the ungovernable sea;

Heart mysteries there, and yet when all is said

It was the dream itself enchanted me:

Character isolated by a deed

To engross the present and dominate memory.

Players and painted stage took all my love

And not those things that they were emblems of.II

Those masterful images because complete

Grew in pure mind but out of what began?

A mound of refuse or the sweepings of a street,

Old kettles, old bottles, and a broken can,

Old iron, old bones, old rags, that raving slut

Who keeps the till. Now that my ladder’s gone

I must lie down where all the ladders start

In the foul rag and bone shop of the heart.

The entire poem is written in eight-line stanzas, abababcc, a form known as ottava rima. The stunning, to me, rhythmic aberration in the poem occurs at the end of the first section:

Winter and summer till old age began

My circus animals were all on show,

Those stilted boys, that burnished chariot,

Lion and woman and the Lord knows what.

In these lines there is a modest catalogue of a circus parade: boys on stilts, decorated chariots, lions, (sequined) women, and then: “and the Lord knows what.” I suppose one can read the final line of the stanza as alternating stresses and unstresses in some varied form (technically the line begins with a trochee, proceeds to an iamb, goes on a tribrach – three unstressed syllables – and ends with a molossus. Nope, these things do not come easily to mind: I had to look them up.) It has always seemed to me worth considering that those final three words are all stressed, a remarkable ending to an overwise lovely stanza. Jarring. Like the thought that his circus animals, the decorative figures of esthetic amusement he has created all his life, no longer suffice. Full stop: Bang. Bang. Bang.

Let’s go back: What of that first section? It contains the whole poem. Based on a remarkable conceit (a conceit is complex or unexpected figure of speech), Yeats as an old man considers his long career as if he were not a ‘poet’ but an entertainer, parading out all sorts of ‘circus animals’ to invite and entertain readers. But the circus animals no longer come to him (think of the title: “The Circus Animals’ Desertion”). He is old, broken. Broken.

Yeats, with the bravado of middle age, famously proclaimed in “Sailing to Byzantium” that in old age men were frail-bodied an, because of the temporality of the flesh, in need of the esthetic, the ideal:

An aged man is but a paltry thing,

A tattered coat upon a stick, unless

Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing

For every tatter in its mortal dress. . .

But that is not what we find here, not in this poem of his actual old age. Here he is old, broken, and as the entire stanza reminds us, and the second section tells us, the esthetic of using glorious words and imagery doesn’t work any longer. All he has is his “heart.”

Maybe at last being but a broken man

I must be satisfied with my heart, although

Winter and summer till old age began

My circus animals were all on show…

As I wrote a moment earlier, he has a kind of writer’s block: all that he practiced, all that he could call upon, in his great career as a poet now fails him. All he has is his heart.

So we are set up, in the first section, for the last section. But that final section is glorious almost beyond belief – I don’t think, despite the forewarning, we are prepared for this – when all he has is his heart.

III

Those masterful images because complete

Grew in pure mind but out of what began?

A mound of refuse or the sweepings of a street,

Old kettles, old bottles, and a broken can,

Old iron, old bones, old rags, that raving slut

Who keeps the till. Now that my ladder’s gone

I must lie down where all the ladders start

In the foul rag and bone shop of the heart.

Yeats is not one for false modesty. When he wrote this poem, he was the greatest poet writing in the English language. It is not an idle claim when he says of his poems and plays that they are based on “masterful images” and are complete. And yes, they grew out of his desire to turn life into art, to make things beautiful. He articulated his task in the beautiful dialogue that appears in his relatively early poem, “Adam’s Curse:”

‘A line will take us hours maybe;

Yet if it does not seem a moment’s thought,

Our stitching and unstitching has been naught.

Better go down upon your marrow-bones

And scrub a kitchen pavement, or break stones

Like an old pauper, in all kinds of weather;

For to articulate sweet sounds together

Is to work harder than all these…’

Ah, the artist. As I said in a long discussion recently about art and life with my friend Tom, art heightens life, makes what slides by us memorable – and permanent. (I learned that from Rainer Maria Rilke, grudgingly. But I did learn it. From his “Ninth Duino Elegy,” which I have discussed before.)

That is not the Yeats whom we encounter, here, in the final section of the poem we are looking at. Poems are not merely masterful images. They may have masterful images, but they contain elements of their origin in the human heart.

Hmmm. Does it seem exceptional to proclaim, as if one is discovering a great truth, that poems ‘contain elements of the human heart’? Listen to Yeats, for what he realizes about the heart is extraordinary.

First, a relatively long byway. One reason I so love Wordsworth is that he uncovered childhood, recognized that we do not put it aside as we grow older, but carry it within us. One hundred years before Freud, he knew and articulated much of what Freud would ‘discover.’ There is that wonderful short lyric, with a line that seems relatively pale until we concentrate on it and its revolutionary illumination: “The Child is father of the Man.” What? This is counter to all we think we know, which is that men father children. That would seem to be the natural order of things. But listen to Wordsworth:

My heart leaps up when I behold

A rainbow in the sky:

So was it when my life began;

So is it now I am a man;

So be it when I shall grow old,

Or let me die!

The Child is father of the Man;

And I could wish my days to be

Bound each to each by natural piety.

But let me turn, when considering childhood and Wordsworth, to these famous lines from The Prelude, written in 1805:

Fair seed-time had my soul, and I grew up

Foster'd alike by beauty and by fear;

No lines ever written are more telling than these. Our soul, our being, has its roots in earliest childhood. And Wordsworth, depressed following the turn to the ‘Reign of Terror’ of the French Revolution, in the long poem The Prelude is trying to understand why he still seeks joy and meaning in life. So he returns to his childhood, when he was fostered by beauty – and by fear. He gives us instances of both; literary critics, seeking to understand his romanticism, stress the ‘sublime,’ his understanding that fear and terror are a part of beauty.

Nonetheless, for Wordsworth, childhood is good. “Fair seed-time had my soul.” But Yeats, Yeats in this poem presents a different picture. The heart is a “foul rag and bone shop.” All the detritus of our lives has a place there, and the detritus stays with us and forms us. It is the ground underneath all we build; it is the ground on which all our ladders stand when we seek to climb above the mire.

There is no climbing, says Yeats. Our hearts are what we have, what we depend on. In this, he is like Wordsworth. But how much difference a century and a half have made! For Yeats, the heart is filled with the junk and cast-asides of the lives we live. And no matter how we try to ennoble the heart, it remains a storehouse of all we have encountered in life.

Ah, but it is not this ‘idea’ that makes this final section so compelling, such a high point (if I may use that term in referring to what is deep and beneath) in human artistry. What is compelling is the catalogue that Yeats compiles of what is in the heart: the trash we have encountered in our lives.

A mound of refuse or the sweepings of a street,

Old kettles, old bottles, and a broken can,

Old iron, old bones, old rags, that raving slut

Who keeps the till.

Each time I encounter this catalogue it takes my breath away. “A mound of refuse.” Street sweepings. Stuff that we thought we had discarded, and discarded as worthless: “old kettles, old bottles” and “a broken can;” “old iron old bones, old rags.” And all, as in a horrible junk shop, superintended by “that raving slut/ Who keeps the till.” Our heart is both the place where the garbage of our life is stored, for sale to the poet who must root himself in his actual life, and the custodian of that garbage, that junk. Insane, beyond – as Nietzsche would say – beyond good and evil and all considerations of morality. “That raving slut.”

(I don’t think his great contemporary T. S. Eliot learned from Yeats. True, he began “East Coker,” one of his Four Quartets with the famous line “In my beginning is my end,” and concluded it “In my end is my beginning.” These are lines he appropriated – he wrote, famously, “Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal” – from a 14th century French song, Machaut’s “Ma fin est ma commencement.” Eliot’s The Waste Land is filled with images of trash – “A rat crept softly through the vegetation/ Dragging its slimy belly on the bank/ While I was fishing in the dull canal/ On a winter evening round behind the gashouse,” and all sorts of literary garbage he later summarizes as “These fragments I have shored against my ruins” – but for Eliot the trash is literary. He hid well the trash that his heart contained….)

The critic and theorist Viktor Shklovsky said, in the early years of the twentieth century, that poetic language slows us down, demands of us that we consider and reconsider what we encounter, that we need to think hard and not easily – as if by formula – about life. Almost a century later Daniel Kahneman in Thinking, Fast and Slow, made a similar point about not poetry but homo economicus: we fall into formulas for thinking. Thinking fast is a technique we have adopted to master the complexity of our lives, to respond adequately to all that confronts us. But sometimes we need to slow down, he says, or what we think will falsify what we encounter.

So let us think slowly about this remarkable catalogue that Yeats has given us in the final stanza of “The Circus Animals’ Desertion.”

A mound of refuse or the sweepings of a street,

Old kettles, old bottles, and a broken can,

Old iron, old bones, old rags, that raving slut

Who keeps the till.

This, says Yeats, is what we carry around within us. All those episodes we think we have forgotten, moved on from: all that “trash” that we try to move on from. Here is what Sylvia Plath says of it in “Lady Lazarus:”

What a trash

To annihilate each decade.

Plath, though, could not annihilate the trash. She committed suicide. Yeats understands that we cannot get rid of all that has happened to us, to all the garbage of our past. We carry it within us, not just as it shapes the heart, but as the contents of our heart.

“A mound of refuse.”

And with nothing redeeming, as we like to think, as Wordsworth claimed, for he saw and felt that in childhood lay his seeming salvation. Nothing. Just trash, the detritus of our lives. What is left as we confront our past is “the sweepings of a street.”

Old iron pots, “kettles.” Bottles not returned, and cans misshaped by can openers, misuse, the rust of time. “Old bottles, and a broken can.”

Metal stuff – “old iron” – and the bones and rags of our previous selves and from those we have known in our past, disheveled and worthless, yet within us all the same. “Old bones, old rags.” We do not escape our past, we just store it deep within us.

And we keep account of what is in that storehouse, maddened by our imperfect and corrupt intercourse with the world. “That raving slut/ Who keeps the till.”

That catalogue is the essence of this poem, and what Yeats has to tell us in this poem. We live with the trash; it is not, as Plath had hoped, “annihilated each decade.”

Yeats tells us that is where good poems, authentic poems, come from.

Now that my ladder’s gone

I must lie down where all the ladders start

In the foul rag and bone shop of the heart.

We carry within us all that we have experienced, all that we have encountered. We can make “masterful images” out of ourselves, for ourselves, but in the end the ground of our being, the ground on which all artful ladders start, is “the foul rag and bone shop of the heart.”

What is wonderful – ah, no beating about the bush, ‘stupendous’ – about Yeats’ conclusion is that it recognizes how we, each of us, have a lifetime of experiences and encounters that we carry within us. Unlike Wordsworth, these experiences do not add up to ‘fair seed time.’ Unlike the promise of psychoanalysis, which is that by recognizing the baggage we can move beyond its harmful effects, there is no going-beyond.

We are, we depend on, we must root ourselves in, our own awkward and unpleasant history. “Foul” that rag and bone shop is, “foul.” All too often we think we can ‘transcend’ our beginnings, and our past. For Yeats, in this poem, there is no transcendence. What he has is himself, which is quintessentially and unavoidably every item in that “foul rag and bone shop” he carries within him, within and beneath consciousness. In his “heart.”

In one sense, the poem’s ending can be seen as depressing. We all strive for, hope for, transcendence. This poem does not, emphatically, end with transcendence.

In another sense, though, Yeats is heroic. We must live with ourselves, accept ourselves, understand that to be a human being is to live in this world, not in some far-off, hoped-for other.

Yeats, late in life, went beyond Mallarmé. It is not the voyage to ‘elsewhere’ that we must finally attempt. The acceptance of the self, with all the trash it entails, is what our lives ultimately come to. Yeats, like du Bellay so long before, understands that coming home is more significant, richer, than voyaging abroad. Even if that coming home is to “the foul rag and bone shop of the heart.”