Ravel’s “Le Tombeau de Couperin” and what it teaches us about war

One of the things I find most wonderful about poems is that they enable me, and sometimes force me, to confront views other than my own. In what follows, I make a case for Ravel and his challenging approach to war. I am not sure I agree with Ravel at all, but I can recognize that he has something to tell me. In the letter which follows, I think I honor what he has to say, even if I do not fully believe all I have written in explication of his view.

Maurice Ravel’s Music: Le Tombeau de Couperin

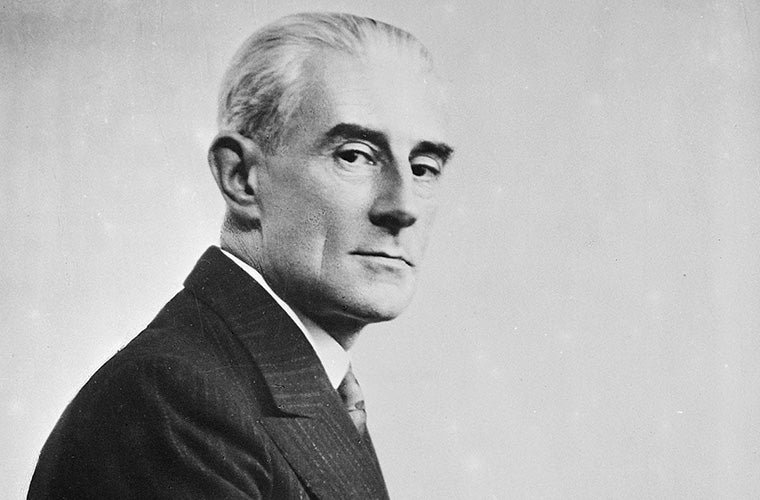

Maurice Ravel

With war raging in Ukraine, and casualties mounting, it is hard to read the news. Or watch the television news shows. So much death and destruction. And more to come. And Putin is threatening (sub voce, but threatening nonetheless) the unthinkable: Nuclear war.

I watched the N.B.A. I have a drink every night. I eat the wonderful dinners my wife prepares. The world, in many ways, goes on, but its backdrop is war and more war. As is clear, I avoid that thought, as so many of us do, and try to live a life of ‘normality.’

In the midst of this weak attempt at coping, I came across Ravel’s Le Tombeau de Couperin. I came to it by a circuitous route, listening to some keyboard pieces by Francois Couperin. Why Couperin? I am not sure, but as I try to push my listening- to-music envelope chronologically I try to push forward to post-modern music, from Ligeti to Reich to Pärt. But I also move backwards as well as forward in time. Going back, earlier than Haydn, earlier than Bach, brought me to Couperin, a wonderful composer who wrote in the early 1700s: An older contemporary of Bach. And listening to him brought me to an early twentieth-century piece by Ravel, who offered a memorial to his predecessor – and an appreciation, since “Tombeau de Couperin” can also mean, ‘Tons Beaux,’ or ‘beautiful sounds.’

I should confess that I do not much like French music, which I think is more concerned with tone color than with sound structure. It was only recently that I gave some credit to Debussy, and that was intellectual rather than emotional: In the momentous move away from tonality toward the atonality that would be the signature[HG1] of modernism, Debussy was a great explorer and advanced practitioner. Without the fuss of Schönberg….

Ravel, I figured, was the slightly later contemporary of Debussy, a tonalist like his French forebears. There was the overly-played and much-lauded “Bolero” and the lyrical “Pavanne for a Dead Princess.”

Then I listened to Ravel’s Le Tombeau de Couperin.

World War One and its relation to this music is what fascinates me.

Ravel tried to enlist in World War One, to no avail. Finally, after much effort, at the age of forty, he enlisted as a truck driver in the French Army. He drove trucks under heavy bombardment. This was no ‘easy service’ for the French composer. He knew war, first-hand. He saw it directly, and not through the lens of ‘the news.’

During and after the war he wrote the Tombeau. It memorializes Couperin, yes, but its primary focus is on six friends of Ravel who died in the war. Each of the six movements is dedicated to one of these friends.

War music can be patriotic, summoning men (and sometimes women) to fight for the glorious motherland. War music can be tragic and elegiac, since war so often occasions tragedy. (In this vein, I often listen to Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem, wondrous music conjoined with the war poetry of Wilfrid Owen. Owen wrote, in the “Preface” he intended for his poems,

This book is not about heroes. English poetry is not yet fit to speak of them.

Nor is it about deeds, or lands, nor anything about glory, honour, might, majesty, dominion, or power, except War.

Above all I am not concerned with Poetry.

My subject is War, and the pity of War.

The Poetry is in the pity.

Yet these elegies are not to this generation,

This is in no sense consolatory.

Owen wrote poems of pity, elegies to those massacred – needlessly, he thought – in the trenches and on the battlefields.)

But to accept that ‘war music’ can be light, flowing, not in the ‘key’ of pity: Who knew?

Well, obviously, Ravel. We can honor those who died in war without beating our breasts, weeping and wailing. We can think of war without having to praise, with patriotic fervor, those who sacrificed what Lincoln called “the last full measure of devotion.” But the actual, lived lives of those who were lost to war are not always, maybe not ever, lugubrious or tragic movements through existence, whatever that ‘existence’ is. The lives of people are quick-silver, ongoing, often lovely. I think Ravel understood this, and in memorializing his deceased friends he honored the lives that they lived.

For people like me, and perhaps you, it is worth remembering that life is not only defined by war, or by the deaths that war occasions. There is something to Ravel’s melodic lightness of touch that we should remember as we try to grapple with the war in Ukraine, and what it means. “I sell you no phony forgiveness,” Ralph Ellison’s protagonist says near the end of Invisible Man. He continues, “I’m a desperate man – but too much of your life will be lost, its meaning lost, unless you approach it as much through love as through hate.” No easy words here, either, for what follows is: “So I approach it through division. So I denounce and I defend and I hate and I love.”

Ravel will “sell you no phony forgiveness.” But he has something to tell us. What he has to say is about life, the life that is interrupted, ineradicably, by war. What comes before mortality also has its claims on us.

Ravel was no apologist for war, and he was not a stranger to what war was like. That he could, would, write Le Tombeau de Couperin is a reminder to us, now, in these difficult times, that war is otherwise than we imagine. And if we try to imagine war and its losses, we could do worse than listen to Ravel…. His work is disquieting, reminding us of dimensions we do not imagine.

My friend, pianist Paul Orgel, recommended a performer of the previous century to me, 1950’s pianist Marcelle Meyer. Here is her rendition of Le Tombeau: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pd49pEjnjS4

Here is a more recent piano version by pianist Louis Lorti with only one photo, a photo I do not really like, though the performance is great: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7cehirUUigg

The orchestrated version is richer, though I prefer the earlier piano version. Ravel only orchestrated the first four movements: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7NA4j3VhGY4