Robert Hayden, “Frederick Douglass”

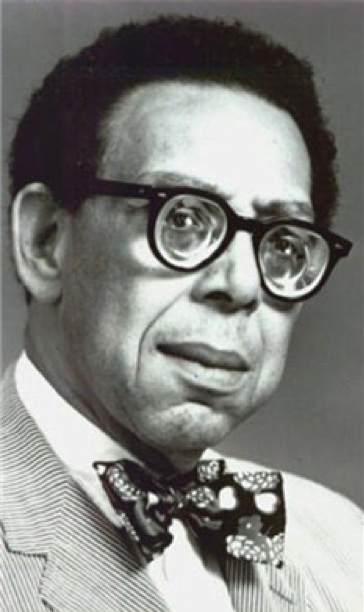

Robert Hayden

Many years ago I taught courses in black American literature. I loved Frederick Douglass, both his autobiography and his speeches. He was, in my deeply held view, one of the greatest Americans.

The midcentury African-American poet Robert Hayden wrote a number of poems that deserve to be in the canon of our nation’s finest works. The poem which I discuss here is one of them. It commemorates a great American. It is, at the same time, a great poem.

As you will see, it runs counter to our prevailing sense that poems should often be difficult, that the knottedness of their thought should in some way mirror the deep ambiguities and ironies of our deeper thinking about human existence. The poem is not hard to understand, but if we do not read it slowly and carefully we miss the many perceptions that are embedded within it.

A story about this poem: Many years ago I was invited to give a series of lectures and seminars in Tunisia. During my two-week stay, Martin Luther King day was celebrated in the United States, and the American embassy in Tunis asked if I would speak briefly at the consulate in honor of that occasion to an audience of Tunisians.

I decided not to ‘speak’ but to read. It was not hard to choose the peroration of King’s great “I Have A Dream” speech, which lives on in the heart of so many Americans, at least of my generation. I then considered reading from what I consider Douglass’s finest speech, in which he celebrated the anniversary of the independence of the West Indies. I love that speech, and my life has in part been shaped by it. But somehow I did not want to put King and Douglass together: this was, after all, King’s day.

Then I thought of Hayden’s poem about Douglass, not because Douglass needed to be represented at the embassy event but because what the poet writes about Frederick Douglass is also true of Martin Luther King. Both men struggled for freedom and equality; both men pushed our nation forward and challenged all of us to commit our lives to freedom and justice..

I read “Frederick Douglass” at that event. No surprise: even set against King’s great words, Hayden’s sonnet held its own as a statement about human struggle and human freedom.

Frederick Douglass

When it is finally ours, this freedom, this liberty, this beautiful

and terrible thing, needful to man as air,

usable as earth; when it belongs at last to all,

when it is truly instinct, brain matter, diastole, systole,

reflex action; when it is finally won; when it is more

than the gaudy mumbo jumbo of politicians:

this man, this Douglass, this former slave, this Negro

beaten to his knees, exiled, visioning a world

where none is lonely, none hunted, alien,

this man, superb in love and logic, this man

shall be remembered. Oh, not with statues' rhetoric,

not with legends and poems and wreaths of bronze alone,

but with the lives grown out of his life, the lives

fleshing his dream of the beautiful, needful thing.

Spring, here in Washington, arrived and is now gone. The miraculous transition is over: even late spring dogwood has faded, and the climax of azaleas has crested, if only just days ago.

The poem that has been in my mind is not, however, about spring. It is Robert Hayden’s “Frederick Douglass.” I can’t say why I have been thinking about this poem in particular. True, it is a favorite of mine, in part because it speaks of history and political struggle, neither of which are frequently the subject of lyric poems, with a directness I respect greatly. Perhaps in part it has to do with my shared admiration, along with the poet, for the great role Douglass played in the shaping of the American republic. In part, I love the poem because of what it sounds like: its rhythms, its assonances and alliterations. I love its wonderful grammar, which enables what is most important in the poem’s first majestic sentence, after ten lines, to appear only when the sentence comes to its conclusion. I don’t think the poem has any ‘Germanic’ overtones, but the structure reminds me of German, where everything is held in suspension until the last word of the sentence: in German the verb, the happening, comes last. A similar suspension reigns here.

Two things surprised me as I considered writing about this poem.

The first of the surprises was that the poem is not difficult. Well, the grammar is. I believe Hayden learned something about grammar from Gerard Manley Hopkins[1].

Once we acknowledge that the grammar is difficult, the poem returns to what I said of it: the poem itself is not difficult. I do not find it full of allusive texture, complex irony, rich ambiguity, those hallmarks of how so many poems are able to speak to us so deeply, to say so much in a modest number of words.

The second surprise has to do with the critical context in which we read poems today. So much of our academic literary stance has to do with theoretical approaches. There is deconstruction, which is a fancy way of saying that if you look very, very closely at what humans say or write, you discover that all there is, is words. Deconstructive critics take our human apprehension that what we say is ‘just words’ and push that hard toward a conclusion that the connection between words and things is arbitrary, and we can never really get from words to things.

There are the ideological approaches, which look to bunch of ‘isms’ to see how everything that is written is inflected by one or more of these isms. These academic approaches seek out the traces of power relations in every literary text. So a Marxist approach looks at class; a feminist approach looks at gender – as does a queer approach; a post-imperialist approach looks at colonial power as a shaping force.

But Hayden’s poem, though it refers to race and though it celebrates a black hero, seems largely resistant to what I would call, changing just one word of his lovely phrase, ‘the gaudy mumbo jumbo of literary theorists.’ Perhaps both these surprises, that the poem is not difficult and that it is straightforward enough to slip by the elaborate ways many critics approach literary texts, are really one and the same: This poem is not a hard one to read, even though as I’ve said the grammar is at first daunting. And yet, as we shall see, because there is a density of ideas that propels the language forward, and because the poem’s economy allows it to say so many things in just over a dozen lines, it is a very rich communication. Hayden tells us a lot in “Frederick Douglass,” both about the man he praises and about the lives we live.

Let me start with history, with who Frederick Douglass was. Douglass was born into slavery at the end of the second decade of the nineteenth century, and escaped from that his owner by heading north toward freedom in 1838. We know about his life up to that point in good part because of a remarkably economical, remarkably moving autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written By Himself which he published seven years after gaining his freedom[2]. Between his escape from slavery and the writing of his autobiography, Douglass allied himself with the great abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. An outstanding orator with a compelling story, Douglass become a leading black voice for the abolition of slavery. The Narrative, one of the masterpieces of American literature, was a testimony then, (as it is now) to the dehumanizing force of slavery, and the strength, resiliency, intelligence and humanity of slaves, represented to the reader by Douglass himself.

Douglass would go on to be one of the earliest and most prominent male supporters of women’s rights, a diplomat, an advisor to presidents. But his most important role was the one he played in the twenty years before the Civil War when his Narrative, and even more his speeches, advanced the cause of the abolition of slavery.

In an era of great rhetoric, Douglass’ West India Emancipation speech, delivered at Canandaigua, New York, on August 3, 1857 has, in my view, no rival but the Gettysburg Address. Here is its peroration, words that have played an important role in my own consciousness for decades, because they speak to the centrality of political struggle in human life.

Let me give you a word of the philosophy of reform. The whole history of the progress of human liberty shows that all concessions yet made to her august claims have been born of earnest struggle. The conflict has been exciting, agitating, all-absorbing, and for the time being, putting all other tumults to silence. It must do this or it does nothing. If there is no struggle there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom and yet deprecate agitation are men who want crops without plowing up the ground; they want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.

This struggle may be a moral one, or it may be a physical one, and it may be both moral and physical, but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will. Find out just what any people will quietly submit to and you have found out the exact measure of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them, and these will continue till they are resisted with either words or blows, or with both. The limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress. In the light of these ideas, Negroes will be hunted at the North and held and flogged at the South so long as they submit to those devilish outrages and make no resistance, either moral or physical. Men may not get all they pay for in this world, but they must certainly pay for all they get. If we ever get free from the oppressions and wrongs heaped upon us, we must pay for their removal. We must do this by labor, by suffering, by sacrifice, and if needs be, by our lives and the lives of others.

Enough on background: Let us now move on to the poem, written in 1947 by Robert Hayden, one of the two pre-eminent African-American poets of that era, the other being Gwendolyn Hughes.

The first sentence of this sonnet – yes, although it does not break down conventionally into an octave of eight lines and a sestet of six, or three Shakespearean quatrains with a concluding couplet, it is a sonnet, determined by its fourteen lines.

Its structure and central argument is, once we parse the grammar, are remarkably simple. ‘When we get freedom….this man, Douglass…shall be remembered.’

The delay of the moment when the kernel of the sentence, its subject and predicate, finally appears is a major element of the poem. “This man shall be remembered” comes only at the end of the tenth line and the start of the eleventh. Why does it take so long to say that Douglass shall be remembered? When we look carefully we see two lists, one prefaced by a series of when’s, another prefaced by a series of this’s, which point to the particularity, the specificity, the historical density of the Frederick Douglass who is the subject of the poem

Here is a longer summary of the sentence, an outline of the poem’s argument. When “freedom…is finally ours,” when freedom “belongs at last to all” and is part of us, “truly instinct,” when freedom is ours because it is “won” and not merely bestowed or accidentally happened into, when freedom is a thing or condition and something more than merely language, “the gaudy mumbo jumbo of politicians”: When these conditions prevail, then “this man,” a “former slave…superb in love,” “this man shall be remembered.”

Most of the time we look to poems for their deep emotional resonance. Many of the best lyric poems combine emotion with an intellectual or perceptual acuity: the poem not only touches us to the quick, but at the very same time it impels us to new understanding of why we have this emotional response or what it signifies. Hayden understands the complementarity of the two sides of our experience, emotion and intellect; he encapsulates them in five words of wonderful line of praise for Douglass, “superb in love and logic.”

Each time I read the poem I marvel at the logic, the superb logic, with which the poem begins. This is the logic of intellection, not just syllogism. Though I hasten to add that surely the logic Hayden is praising in Douglass refers in part to the syllogism on which Douglass’ abolitionist position rests[3].

But there is more to human logic than the logic of syllogism. We can see that larger logic at work in the first two and a half lines, a logic Hayden celebrates.

When it is finally ours, this freedom, this liberty, this beautiful

and terrible thing, needful to man as air,

usable as earth;

Freedom is beautiful (yes, I think we know that, or at least easily let the sentiment roll off our tongues) but at the same time it is “terrible,” filled with terror. Hayden, and Douglass before him, knows that with freedom comes choice, responsibility, an open future. It is a human condition marked by not just by exhilaration but by dread. Hayden the poet knows, like so many who are drawn to art because it is linked to the sublime, that beauty can induce terror[4].

We are less than two lines into the poem, and the complex nexus of freedom/beauty/terror has already been broached. But even before we arrive at a momentary pause with the semicolon in line three, we also confront the necessity of freedom in the easeful yet wonderful phrase, freedom is “needful to man as air,” which is immediately followed by the understanding that freedom is practical and fruitful, “usable as earth.” The connotations of “earth” are, of course, rootedness; the source of fruitfulness; the basis of growth for vegetation; and the supportive ground for terrestrial beings.

So, after three and a half lines, we are ready for Hayden’s continuation of whens:

when it belongs at last to all,

when it is truly instinct, brain matter, diastole, systole,

reflex action…

We may too easily and too quickly slip by the seven words which encapsulate the great struggle of Douglass life unless we read carefully here: the struggle to assure that freedom (the “it” which is repeated five times in the first six lines) “belongs to all.” When it belongs at last to all. Leaping past the semicolon to the next phrase we see that freedom will belong to all only “when it is finally won.”

Do you remember the stirring lines from Douglass’s Canandaigua speech which I quoted earlier? “This struggle may be a moral one, or it may be a physical one, and it may be both moral and physical, but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.” In human communities, in human history, freedom must be won. It is not, as I pointed out earlier, merely granted or happened upon.

And when freedom is “won,” it must “belong to all.” But what does this belonging mean, what does it look like? How does freedom enter into human life? Freedom must, in the view of Douglass and Hayden as well, become not just the opening up of possibilities in which human life proceeds. It must be internalized into how we think, how we feel, how we act, how we exist.

Freedom must become “truly instinct,” an integral part of the workings of our mind and our consciousness (“brain matter”), the underlying condition of our existence each and every day. It must become an essential part of the beating of our hearts, a necessary component of the pumping in and pumping out of that great and vital organ, “diastole, systole.” Freedom must work so deeply in us that it is part of who we are and what we are, larger than thought, deeper than consciousness. It must be instinctual, “reflex action,” part of the way in which we exist and act at every moment in the world.

Now we come upon the shortest phrase in the poem, highlighting by its brevity the central belief (and accomplishment!) of Douglass’ life: “when it is finally won.” Freedom comes only after struggle. If I may, I will repeat Douglass’s stirring words since Hayden’s recollection of them is at the heart of this sonnet:

The whole history of the progress of human liberty shows that all concessions yet made to her august claims have been born of earnest struggle….If there is no struggle there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom and yet deprecate agitation are men who want crops without plowing up the ground; they want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.

Wow. There is poetry in these lines from his Canandaigua speech, and more metaphor in this prose passage than in the poem. But what the poem has, of course, is economy: “when it is finally won.”

I love the next phrase even as it challenges what goes on in the Capitol Hill world in which I work. In a world where everything is overloaded and hyped and spun, where the fate of humankind seems to hang – if we believe what we hear on radio and t.v. and even, alas, on the floor of the Senate – on whether the financial arms of automobile companies can be exempt from financial oversight, as was a major ‘struggle’ this week in financial reform legislation, Hayden shows us a Douglass who functions in a different sphere. He speaks of freedom, he fight for freedom, distant from “the gaudy mumbo jumbo of politicians.” Freedom is more than a word, more than a verbal bishop or knight to be deployed in a chess game of electoral politics, more than a slogan on talk radio.

Let us step back for a moment into a poem which preceded Hayden’s by almost a century. In my view, the most momentous line in all of American poetry comes at the exact center of our greatest poem, “Song of Myself.” After Walt Whitman has been writing about himself for 23 pages in a volume with no author’s name on the cover or on the title page he finally identifies himself by name: “Walt Whitman, a kosmos, one of the roughs.” Similarly, here, at the center of Hayden’s celebration of the great abolitionist, at the center of the poem – line seven of fourteen – he names his subject: “this Douglass.”

Whereas Whitman named himself and then proclaimed himself part of the humanity of which he was an individuated instance – “Walt Whitman…one of the roughs,” Hayden does the opposite in writing of the great abolitionist who is his subject. Douglass is an individual, “this man.” Though just two words, it is not as simple a statement as it might on first glance appear. For surely the great struggle of Douglass’ life, inseparably intertwined with the struggle for freedom, was the struggle to be recognized as a man. Not property. Not a beast for labor. Not less than human, without intelligence, without feelings. A man.

“This man, this Douglass, this former slave, this Negro.” In one remarkable line Douglass and his condition are completely summarized: a man, a man born into slavery, a slave because he was black, and yet for all that a man and an individual human being capable of his own accomplishments: a Frederick Douglass.

The line, which consists of four this’s, four nouns and one adjective – “former,’ a slave no more! – pivots wonderfully to give us a moving image of Douglass in situ as a slave:

this Negro

beaten to his knees, exiled,

Fact, not overstatement; no moving of the reader by the ‘gaudy mumbo jumbo’ of recounting the horrors of slavery. Douglass was beaten to his knees and exiled both from his family[5] and from the human community by being categorized as ‘less than human’ or ‘other than human.’ If one is a slave, one’s bonds with human beings who are defined by freedom and the ability to have some control over their own existence is ruptured.

Douglass (1818-1895) was an exact contemporary of Whitman (1819-1892). In Hayden’s view Douglass had the same commitment to building a world of inclusion and acceptance as Whitman[6]:

this Douglass, this former slave, this Negro

beaten to his knees, exiled, visioning a world

where none is lonely, none hunted, alien

In a path-breaking essay, “Some Lines from Whitman,” the poet Randall Jarrell responded to a passage in Whitman with a response unusual to literary criticism then, and even more unusual in our world today. Jarrell eschewed explanation in words have always resonated deeply for me. He expressed a sentiment that I feel when confronting the lines I have just cited from Hayden, especially the phrase I have highlighted in bold. The passage I am about to cite from Jarrell’s essay begins with lines which conclude Whitman’s description of a dramatic rescue at sea:

All this I swallow, it tastes good, I like it well, it becomes mine,

I am the man, I suffered, I was there.

In the last lines of this quotation Whitman has reached – as great writers always reach -- a point at which criticism seems not only unnecessary but absurd: these lines are so good that even admiration feels like insolence, and one is ashamed of

anything that one can find to say about them.

So let me just cite Hayden’s lines about Douglass’ vision again, and say no more about them or even acknowledge the depth of my admiration:

this Douglass, this former slave, this Negro

beaten to his knees, exiled, visioning a world

where none is lonely, none hunted, alien

We are, I know, going slowly through this short poem. It is, as I said at the outset, richly economical even though it is not difficult.

this man, superb in love and logic, this man

shall be remembered.

I cited this line near the start of our examination of the poem. Now that we have worked through much of the poem, now that we have the poem itself as our context, the line is even richer than it appeared earlier: “this man, superb in love and logic.” For what we see here is that “this man” repeats the prior this man in what we should recognize as an identical rhyme. Four lines previous the pronominal adjective this had introduced Douglass as a man, and thereafter “this man” was identified as the former slave and Negro and ‘Douglass” who envisioned a world far beyond, and totally different from, the world in which he lived as a slave. Now, “this man,” being “superb in love and logic” is a testimony to imaginative transcendence. The lines recognize Douglass’s ability to surmount his own loneliness and exile and envision a world shaped by the deepest love of which humans are capable.

“This man shall be remembered.” The verb for which we have been waiting has appeared. The series of “this’ has been concluded: the sentence is complete. When we have freedom, all of us; when freedom is a part of us; when the long struggle for freedom is over, we shall remember the former slave who envisioned what freedom means. We shall remember “this Douglass” for the fight he led to bring us all to freedom. “This man shall be remembered.”

Oh, not with statues' rhetoric,

not with legends and poems and wreaths of bronze alone,

but with the lives grown out of his life, the lives

fleshing his dream of the beautiful, needful thing.

What follows “This man shall be remembered” seems an addendum. Douglass shall be remembered: the final three and a half lines merely tell us how. But the ‘seems’ and ‘merely’ I just wrote are just that, appearances that Hayden creates by the rhetorical device of using “not.” He will not be remembered with “statues’ rhetoric,” a subtle reminder of the “gaudy mumbo jumbo of politicians.” He shall not be remembered by “wreaths of bronze alone.” He shall not even be remembered – this is being written by a poet, remember, and in a poem – “with legends and poems.” Yes, statues will commemorate him, and their wreaths of bronze. And men and women through time will retell his story until it becomes part of the mythy background of legend. And poets, among them Robert Hayden, will celebrate his life and accomplishments in verse.

“But.” One of the most powerful words in our English language, because it signals that what has been said is going to be modified, or limited, or even contradicted. Douglass will not be remembered most vitally by statues or stories or poems but – in a soaring conclusion –

but with the lives grown out of his life, the lives

fleshing his dream of the beautiful, needful thing.

The poem has circled back to its beginnings, when “freedom” was revealed as “usable as earth.” Douglass is with us today because our lives, shaped by the freedom in which we live, grow out of his, our “lives grown out of his.” Hayden refers most specifically, I think, to the lives of black Americans who live and grow in freedom, who can flower and be fruitful because they no longer are shackled by slavery. One may think back, perhaps, to the ten-year-old Barry Obama, whose life stretched before him as full of promise, a great testimony to what the successful struggles of Frederick Douglass made possible. Douglass’ life has become our flesh, for he has brought us freedom, and in the first five lines of the poem we learned that freedom is only real

when it belongs at last to all,

when it is truly instinct, brain matter, diastole, systole,

reflex action

Yes, we are back to the start of the poem, having traveled full circle from “this beautiful and terrible thing, needful to man as air” to “fleshing his dream of the beautiful, needful thing.”

I think you will recall that at the outset of the journey into this poem, I said that its structure, despite the complexity of its long sentences, could be reduced to “When we get freedom….this man, Douglass,…shall be remembered.” Now we see that the remembrance is not just a matter of ideation, of thinking back on Douglass as a legendary figure. The remembrance is part of who we are. We have, quite literally, incorporated him, taken his life into our own bodies. We are ‘fleshed’ with his vision of “a world where none is lonely, none hunted, alien.” We have grown into this beautiful, terrible, needful freedom because the man who struggled to bring “it” to so many, Frederick Douglass, has made it so. “This man,” to return to the great climax of the poem, “this man shall be remembered.”

Footnotes

[1] Hopkins was a late Victorian British poet who might also be considered one of the first of the Modernists. One reason Hopkins’s grammar is tough to parse is that he attempted to develop a new kind of meter, which he called ‘sprung rhythm.’ Thinking of Hopkins made me aware, as I sat down to write, that this poem, like those of Hopkins, is more interested in strong stresses in the line than in counting syllables. (That old chestnut, iambic pentameter, is the dominant meter in English not just because Shakespeare used it, but because its pattern of five stresses in a line, each preceded by an unstressed syllable – making ten syllables in the line – comes closest of all counted meters to approximating the rhythms of English as we speak it in the course of our daily lives.) In this poem, as in Hopkins, the number of syllables in each line varies widely. A later letter will consider a poem by Hopkins.

[2] He would write two more autobiographies, much longer and not as compelling, in later years.

[3] The syllogism runs in this way: ‘Any biped with a face, prehensile thumbs and the ability to speak is a man. Americans of dark complexion are bipeds with faces, prehensile thumbs, and the ability to speak. Therefore, Americans of dark complexion are men. (And not animals or property.)’

[4] Wordsworth expressed this when he wrote of his early years, “Fair seed-time had my soul, and I grew up/ Fostered alike by beauty and by fear.” A hundred and twenty years later Yeats expressed it in his great elegy, “Easter 1916,” when he used the haunting and memorable refrain, “A terrible beauty is born.”

[5] As so very, very often happened when slaves were property. We may too easily forget that in the twenty years before the Civil War the largest cash crop in agricultural Virginia was … Negro slaves.

[6] In section 24 of “Song of Myself,” the section which begins with Whitman naming himself, he goes on to describe his calling, which is to act as the voice of those who are voiceless. It seems to me one of the great visionary passages in all of literature, and so I will cite it here – particularly because we are about to encounter another great visionary passage, this one in Hayden’s poem. Whitman is proclaiming his role as a poet, to be a spokesman for all:

Through me many long dumb voices,

Voices of the interminable generations of prisoners and slaves,

Voices of the diseas'd and despairing and of thieves and dwarfs,

Voices of cycles of preparation and accretion,

And of the threads that connect the stars, and of wombs and of the

father-stuff,

And of the rights of them the others are down upon,

Of the deform'd, trivial, flat, foolish, despised,

Fog in the air, beetles rolling balls of dung.

Those final three lines, espousing Whitman’s commitment to the whole of humanity – no one excepted, no one left out – and then to the whole of existence, even the ephemeral fog and the low and disgusting beetles feeding on excrement, those lines are exhilarating, a vision which we can and should, each of us, strive to make our own.