Wordsworth’s Prelude, Book One

I’ve been writing these ‘poetry letters’ for ten years. One of my most faithful readers is my son, David. I know he is a faithful reader because he keeps quoting lines of poems I have discussed – even when I don’t remember having discussed them. It gladdens my heart.

Last summer my wife and I went to Seattle to visit David and his fiancée. [They got married three weeks ago, here in Vermont. Bragging, I suppose, I am going to put a photograph of the bride and groom here:]

When I was out in Seattle, we went to its premier bookstore, the Elliott Bay Book Company. Meandering among the remaindered books, I found a lushly illustrated copy of William Wordsworth’s The Prelude. I think it was a vanity project by one of the book’s editors, a wealthy corporate financier. In any case, it had the text of The Prelude and lots, lots, of paintings, etchings and drawings contemporary with it. I bought the book for David.

Now The Prelude is a very long work: It was meant to be an epic, or the prelude to an epic. There was no way I was going to hand it to him without some sort of explication to help him read it.

Why I gave it to him was no mystery, at least to me. The Prelude is my favorite poem. I has been my constant companion for a lifetime. Some of it is, as I discovered in rereading it, turgid. All of it, even though it is written in Shakespearean/Miltonic blank verse, is relatively unadorned: The mellifluous delights of Keats’s “To Autumn,” about which I was currently writing, are not a major feature of the lines. And yet, and yet, Wordsworth was pursuing deep truths, and I think he found them.

Half of the deep insights and the delights of The Prelude come in “Book One,” so that is where a reader should begin.

To help David read “Book One,” I told him I would write about it, and then write about further books as he was prepared to read them. It was, for me, one of the high points of my teaching life: A one-on-one seminar with my own son, about a work that is of surpassing greatness. Who gets to teach a seminar to one’s son? What an honor, what a delight!.

My wife asked to read what I had written for David, so of course I gave it to her. And she said, “This is very good. Why don’t you send it to your poetry letters list?”

That’s why you are getting a letter I originally wrote for my son alone.

One note: “Book One” is long, so I am NOT including the text in this letter (my usual practice), or the letter would be so lengthy no one would read it. Instead, I will give a reference to it below, so you can read it if you wish. There were several versions (I discuss this in what I wrote to David), and this one is the text of 1805. [This text is not exactly aligned to the line numbers below. To see the ‘scholarly’ reason why, read this footnote [1]– or, since it is scholarly, just skip it.]

[1] This is a situation I would much prefer not to be in – an extended discussion of copyright law and textual matters. And what follows is, well, not the sort of stuff that my letters ever take up: A scholarly approach, which as you know I usually find anathema to those who want to read poetry because it matters to them, and too often are put off by excessively specialist jargon.

In the letter, you will find that there were several editions of The Prelude – four, to be exact. The first entire Prelude was written in 1805. The ‘final’ and published edition was in 1850. The best version is, I think, the 1805 Prelude, and this was the one I bought for my son….

Alas, the 1850 Prelude was published – you can do the math – over one hundred and seventy years ago, and is so out of copyright. And so is reproducible, easily, without fee. But the 1805 Prelude first surfaced in a remarkable version by Ernest de Selincourt, who put the 1805/1850 texts on facing pages. It was first published in 1928, and so the copyright on that text has expired, I think. [Copyright law is very complex.]

BUT a newer and more scholarly text, edited by Jonathan Wordsworth, M.H. Abrams and Stephen Gill, but based on the de Selincourt edition, was published in 1979. That of course is STILL IN COPYRIGHT. And this is the edition which supplies the line numbers in the essay.

What is available on the web, not a text, it appears, in copyright, is pretty much similar to the ‘scholarly’ text. I find that its line numbers are sometimes off by three lines, and the words/capitalizations are slightly different. So you can do well by reading the on-line version I sent, since it is quite readable. But if you want the exact text and line numbers I refer to, they are in the edition published by Norton called The Prelude: 1799, 1805, 1850, edited by J. Wordsworth, Abrams and Gill. The “Book First “ in that edition, with facing pages of the 1805 and 1850 edition, is available online here: The Prelude I-II.pdf (armytage.net). So for those of you who crave exactitude and scholarly accuracy, that’s where to go. On the other hand, as I said, if you want an easily readable version of the “Book First” of the Prelude, read the version at http://triggs.djvu.org/djvu-editions.com/WORDSWORTH/PRELUDE1805/Download.pdf . Or, alternately, you can just read the letter, which quotes the poem quite copiously….

Yikes.

Wordsworth’s Prelude

Introduction. Book One.

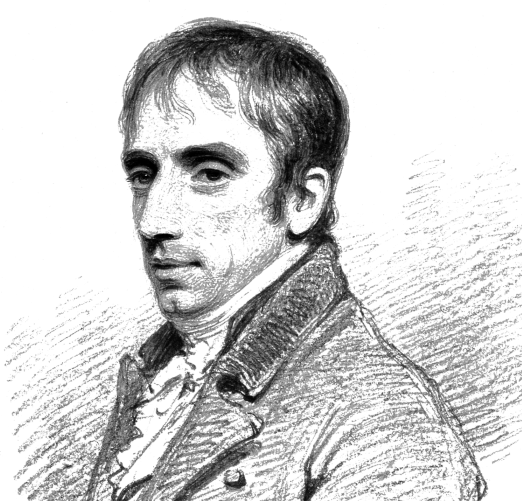

William Wordsworth is the greatest English language poet of the past 250 years. I once disliked Wordsworth intensely, passionately. My route toward and into his poetry was circuitous.

When I was in college, I took an introductory English literature course. As we said then, everything from Beowulf to Virginia Woolf. The twentieth century, more or less, did not exist. We read several Romantic poets – Keats, Shelley, Wordsworth, and the pre-Romantic Blake. I hated Wordsworth: So flat, so unpoetic, so lacking in poetic pyrotechnics.

And then I took a year-long course in Romantic poetry. Shelley I loved, Keats was good, Coleridge was ok – and I still hated Wordsworth. We read Wordsworth’s Lyrical Ballads (I love them now, but found them simplistic then) and also the famous Preface from the second edition to those ballads. We read The Prelude. A long, long poem, an epic even, by a poet I disliked. I remember I had to write two papers on the early books. Ugh. I did not see what the fuss was all about. Wordsworth was to my mind, well, not a very good poet.

I still recall, with great clarity, when I got to the last book of The Prelude. Deep into the evening Wordsworth climbs a peak in Wales, Mount Snowdon so he can be in place to see the sunrise from a viewpoint on top of the mountain. He climbs, and climbs. All is foggy. Then, suddenly, the clouds part, for he has climbed above them, and the light of the moon is cast over everything. Enlightenment for the poet: He knows, at that instant, what he is about, what being a poet means.

I still remember how I felt when I read those lines. They are, I think, not the best lines in The Prelude, but my enlightenment matched his. I felt I knew what Wordsworth was doing and celebrating, and from that day to this I have loved Wordsworth above all other poets. Odd. At one time in my life I read a good bit about Zen Buddhism, and Zen has a thing called satori. It means, I believe, enlightenment, and in Zen it comes when unexpected, when one has given up the effort, the striving, to understand Zen.

I have always thought that Wordsworth had a moment of satori on Snowdon. He has other such moments in the poem, as you will see. But that sudden clarification, the world and the clouds beneath his feet, was a moment of satori. And it was, as I have just tried to relate, a moment of satori for me, too.

Two poets’ words have guided my life. I am not sure I would have liked either of the poets, had I met them when they were alive. One is Walt Whitman, whose words, as he predicted, “ring in my ears.” Matthew Arnold, a Victorian poet and one of the best essayists-on-literature who ever lived, wrote that certain passages in literature are what he called ‘touchstones.” By that he meant that there are things – predominately porcelain – against which rocks can be rubbed to see how hard they are: Touchstones. And certain passages of literature are the things against which we ‘measure’ our lives: What is real, what is significant, what the things of our lives might mean. For me, those touchstones overwhelmingly come from Whitman and from Wordsworth’s The Prelude. T. S. Eliot, in a famous line about the emptiness of modern life, wrote “I measure out my life by coffee spoons.” Coffee spoons are not for me; I measure out part of my life by the phrases I recall from Whitman and Wordsworth. The two are good guides: They understood things about life that I am continually discovering or realizing.

On to The Prelude. To start with, there are two versions, those of 1805 and 1850. Well, there are actually four, as I shall now explain.

He began the poem as an ‘explanation’ of himself to his friend Samuel Taylor Coleridge. A Two-Part Prelude, discovered in manuscript and dating to 1798, was the first go. Then a Five-Part Prelude came next. In 1805 he revisited what he had written, added a lot more, and so wrote the whole poem. He gave this 1805 version to Coleridge to read, and then to his sister Dorothy. Over the next 45 years, he made revisions to strengthen it, although in my view he was mostly concerned with editing out embarrassing parts, particularly about a love affair which he had fictionalized as a part of the poem. A good number of his poet friends read it in manuscript. In 1850, after his death, it was finally published and given a title, The Prelude. The subtitle is more apt: “Growth of a Poet’s Mind.”

Why didn’t he publish it during his lifetime, since it would turn out to be his most momentous work? I think it was too private, and too focused on himself and his personal history. (Keats in a famous letter said that Wordsworth, whom he admired, wrote in the “egotistical sublime.” Wordsworth did not read that letter, but he knew what Keats was talking about…)

I also think it was too early, historically, to write an autobiography, although St. Augustine had written one millennia before, and Rousseau had written an autobiography (entitled the Confessions, like Augustine’s work) a few years previous. But then Rousseau was a radical and a scoundrel and Wordsworth would not have been willing to see him as a forebear. Wordsworth, as a good Englishman, was committed to values like privacy and reserve. He was loathe to write too directly about his own upbringing and about enthusiasms he later regretted.

So Wordsworth didn’t publish The Prelude. Too self-centered, too much revealed about the poet, too revelatory in a direct fashion of who he was and what had shaped him. (As a reminder of how straitlaced the world was, it was only in 1855 that Whitman dared publish Leaves of Grass with “Song of Myself,” and although its first line proclaimed, “I celebrate myself,” the world did not celebrate him.) So: Wordsworth wrote The Prelude in 1798-1805, made minor revisions, and left it after he died for others to publish.

The version you have is the 1805 version. It is better than the later version: Most of his revisions diminished the text, although some improved it. [This was to David, about the book I gave him. In the prologue to this letter, I refer you to a web link that will take you to the 1805 Prelude. Here is the link again: 1805 Prelude. ]

As I told you, there is a lot of dross in the opening pages, and they can probably be skipped. He starts out feeling a breeze as he is walking, and thinks of an Aeolian harp, an instrument whose strings resonate as the wind passes over them: Outside wind, inner music. Whatever. Literary scholars make much of these things. He does tell us, importantly, in lines 6-8, that “A captive greets thee, coming from a house/ Of bondage, from yon city’s walls set free,/ A prison where he hath been long immured.” (in a later version the imagery is yet more clear: “escaped/From the vast city, where I had long pined/A discontented sojourner; now free,/Free as a bird….”) and then says, that as he walked northwards from London, “ The earth is all before me.” [l. 15] English majors often take note of this line, for Milton ended Paradise Lost with “The world lay all before them,” harking back to the Bible where Adam and Eve are cast out of the Garden of Eden with the earth before them. Hmmm.

He will wander like a cloud (he wrote a poem about that, which we will get to before this letter ends), naturally, aimlessly, “The heavy weight of many a weary day/Not mine.” I should note that Romanticism – and Wordsworth was the great English Romantic – had its roots in the discontent and weariness of city life, and often was to find – The Prelude is a great exemplar – salvation from the ills of this discontent in a return to nature and the ways of rural folk. Those are the great subjects of his Lyrical Ballads of 1798.

Wordsworth thinks, walking, that the external breeze has stimulated a correspondent inner breeze, which we might call the divine wind of inspiration. “Thus far, O Friend!” he opines to Coleridge, and lies upon the grass for a whole day before returning to walking northward toward the Lake District, where had spent his early youth. Ah, he had “a cheerful confidence in things to come.” [67]. But the inner breeze, the inspiration, has gone: “but the harp/Was soon defrauded.” Well, it was a nice walk and he had experienced a nice day lying about. Still, even though he revels in “the life/ In common things” [117], he is ambitious and wants to write a great, an epic, poem.

But he has writers’ block, as we call it. Not only do the breezes within cease, but the strong feelings he has had are like heat lightning or even more a false dawn: No storm or sunrise, but “gleams of light/ Flash often from the East, then disappear/And mock me with a sky that ripens not/Into a steady morning” [134-137]. He ought to be able to write a great poem since “as becomes a man who would prepare for such a glorious work… I neither seem/To lack that first great gift! The vital soul” [157-161]. No lack in self-confidence there!

Thereafter he searches for a theme, for pages and pages: He considers long ago tribes, a Miltonic epic rooted in the Bible, tales from Greek or Norse mythology or even a “philosophic Song/Of Truth that cherishes our daily life” [230]. Oh dear, all lines that you can skip. He figures maybe when he grows older – “mellower years will bring a riper mind/and clearer insight” [237]: Maybe he can write, but for now, well, he lives with “mockery…infinite delay…betray[al]…dupe[d]…false.” In a phrase, “blank reserve” [248] or alternately, ‘vacant musing”[255].

He is very hard on himself:

Far better never to have heard the name

Of zeal and just ambition than to live

Thus baffled by a mind that every hour

Turns recreant to her task…

Or see of absolute accomplishment

Much wanting—so much wanting—in myself

That I recoil and droop, and seek repose

In indolence from vain perplexity,

Unprofitably travelling toward the grave,

Like a false steward who hath much received

And renders nothing back. [257-271]

So, what is a poet who cannot write? Not much. He is depressed, baffled, balked. Wordsworth is afflicted with the drying up of inspiration, with writers’ block – just when he thought he was free of the city and his despair. But in his complaint lies his solution. This is where the real Prelude begins. He feels like that “false steward” who has received much and “renders nothing back.”

The question springs up in the next phrase: What did he get or have that he is a “false steward” to? He asks this question, referring to the river Derwent that marked the country of his childhood. (This is where the Two-Part Prelude of 1798 begins!)

—Was it for this

That one, the fairest of all Rivers, lov’d

To blend his murmurs with my Nurse’s song…

For this, didst Thou, O Derwent! travelling over the green Plains

Near my ’sweet Birthplace’, didst thou, beauteous Stream

Make ceaseless music through the night and day

Which with its steady cadence, tempering

Our human waywardness, compos’d my thoughts

To more than infant softness, giving me

Among the fretful dwellings of mankind,

A knowledge, a dim earnest, of the calm

That Nature breathes among the hills and groves. [271-285]

Wow. He recounts how when he was young the wonders of nature made a “music” that “composed my thoughts to more than infant softness.” And that sense, of early harmony and steady peace, gave him the strength to live in the city, “among the fretful dwellings of mankind.”

Wordsworth recalls those wonderful days of childhood when he “Made one long bathing of a summer’s day” and ran about in fields and groves half naked, literally rain or shine. And climbed cliffs and mountains. He goes on to these extraordinary lines, among the finest any poet has ever written:

Fair seed-time had my soul, and I grew up

Foster’d alike by beauty and by fear [305-306]

We are still at the question, “Was it for this” that the passage preceding had begun with. Here we come, I feel, upon the very center of Wordsworth: His understanding that early childhood shapes us, that what we experience in infancy and youth are the “seed-time” from which the ‘plant’ (there is a metaphor here) of adulthood will grow. If we had “fair seed-time,” then the early formation of our life will condition all that comes afterwards.

Note that Wordsworth is not Pollyanna here. If there is harmony (the word will come up, later, and is related to that ‘ceaseless music’ he has just written about), there is also ‘fear.’ For it is through fear, the fear that marks our early years as much as the beauty, that we are shaped. That fear? We are all little people among giants, helpless creatures wholly dependent. Wordsworth understands this. But we are also ‘foster’d’ by fear, which following passages will make clear. Fear teaches us the principles of ethics, of what we ‘ought’ to do.

I guess I cannot stress enough the importance of what is going on here. Wordsworth is discovering childhood. [The under-appreciated Dutch phenomenological psychoanalyst J. H. van den Berg, in a remarkable book The Changing Nature of Man, wrote that even ‘who’ we are as humans changes in historical time. He considers the changing relations between adults and children: How we define who we are is something determined by historical and cultural contexts. How we feel – the particular form our emotions take – is also historical. So ‘discovering’ childhood is an important moment, not only historically, but for understanding ourselves today.] One hundred years before Freud, Wordsworth understood that our experiences in early childhood shape our consciousness, shape who we become and how we act as adults. His brief, famous poem about a rainbow is clear evidence of this:

My heart leaps up when I behold

A rainbow in the sky:

So was it when my life began;

So is it now I am a man;

So be it when I shall grow old,

Or let me die!

The Child is father of the Man;

And I could wish my days to be

Bound each to each by natural piety.

Remarkable line: “The Child is father of the Man.” It reverses the seemingly natural expectation, that men father children, and says that each man was once a child, and that this ‘child’ shapes who the man is to become.

This is the ‘gamble’ of The Prelude, and leads toward our recognition that Books One and Two, which trace his childhood years, are the most important parts of the whole epic poem. What he is telling us is that his early experiences shaped how he relates to the world, what he expects from the world, when he is an adult. His early years were spent in ‘nature,’ and so it will be to nature and to childhood that he returns when he tries to figure out what went wrong. (Remember: He lived too long in the city, and now he is unable to get in touch with his inner self and lacks the inspiration that would enable him to write a poem. And he had started out so well: “Was it for this….”).

It is a hard and important lesson: That what we experience shapes us, and that our formative experiences – what happens in those childhood years – are determinative of who we are and what we struggle with and what resources we can call upon. Sigmund Freud understood this; I have wrestled with Freud’s emphasis on potty training and infantile sexuality, but he understood that when we are very young we develop our relation to our own bodies. How we relate to our bodies is something that we carry with us all our lives. (Jung, on the other hand, was uncomfortable with that notion that even infants have bodies and have a relationship with those bodies; he dropped infantile sexuality for deeply imprinted mythology, which he called archetypes. He was not entirely wrong – the brain itself is structured by neural networks and possibilities – but the archetype of ‘mother’ has a lot more to do with the actual mother we have than with some pre-existent shape of motherhood. What differentiates Freud and Jung is the imprint of actual history: The former recognizes its importance, the latter shrugs it away.) Wordsworth invented the tradition that Freud would later join. There is a saying, ‘biology is destiny.’ Not for Wordsworth: well, not entirely. Childhood shapes our destiny. What we want as infants, what we experience of human relations in our earliest years, lays down patterns and expectations that all our adult relations – with the world, with others – will be built on. Melanie Klein, an important follower of Freud, with her stress on ‘object relations,’ also built on Wordsworth’s basic insight.

I’m sorry to go on to such length, but I think that here is the hinge point where our modern Western culture comes into being, and why Wordsworth is such a fundamental character in the emergence of modernity. We live in his shadow, even today. “Fair seed-time had my soul.” We grow, as plants do, from the sprouts that emerged early in our chronology. Not everyone has “fair seed-time,” but we all are “foster’d” by our earliest experiences.

[It is time for a historical check. Wordsworth’s mother died when he was very young, age seven; his father died when he was thirteen. Loss, then, is a shaping experience for Wordsworth, and he always searches for what has been lost. But he barely mentions his mother in the poem; he deals with his father in a very odd section of Book Eleven, which we will get to when we consider the “spots of time” he provides us. The Prelude recalls that time when at an early age he went to school in the Lake District in northern England, and was happy there. So for him, nature as mother will loom immensely: The natural world replaces the mother he lost.]

Let’s go back to the poem. There is a lot of youthful killing and stealing. In lines 310 and following, he recounts how he used to run ‘wild’ among the hills, trapping woodcocks (‘springes’ are traps for the birds). He was kind of ruthless, a killer of birds: “I was a fell destroyer.” He felt bad about this at the time, “anxious…hurrying, hurrying onward…a trouble to the peace/That was among them.” He felt worse when he stole birds from the traps of others, and nature seemed to pursue him, for he tells us he “heard among the solitary hills/Low breathings coming after me, and sounds…steps/Almost as silent as the turf they trod.” [329-332] He stole bird eggs from nests, a “plunderer,” [336] yet in doing so – getting eggs from birds’ nests on rocky crags – he experienced the sublime (beauty mixed with terror) aspect of nature, “Though mean/My object, and inglorious, yet the end/Was not ignoble,” [339-341] as he hung on the cliffs: “shouldering the naked crag….the sky seem’d not a sky/Of earth, and with what motion mov’d the clouds!” [346-350]

Ah, he was shaped by those experiences. I mentioned ‘harmony, earlier. Here it is:

The mind of Man is fram’d even like the breath

And harmony of music. There is a dark

Invisible workmanship that reconciles

Discordant elements, and makes them move

In one society. [351-355]

What Wordsworth is saying here is that we integrate all our experiences into something that we today (not he, then) call the ‘self.’ All those strange things, even disparate things, even things that do not seem to hang together or perhaps even things which contradict each other, come together in “the mind of man” as if a musical composition were being composed. And so it is. That “one society,” we call the self. Me. Feeling myself to be a unity, harmonious with myself, despite “discordant elements.” It is one of the great mysteries of being, that “discordant elements” can be parts of what we feel to be our unitary self.

Quite wonderful,

that all

The terrors, all the early miseries

Regrets, vexations, lassitudes, that all

The thoughts and feelings which have been infus’d

Into my mind, should ever have made up

The calm existence that is mine when I

Am worthy of myself. [355-361]

A self. Me. Calm. And for Wordsworth, motherless at seven, it is Nature that did this nurturing.

That Nature, oftentimes, when she would frame

A favor’d Being, from his earliest dawn

Of infancy doth open out the clouds,

As at the touch of lightning, seeking him

With gentlest visitation; not the less,

Though haply aiming at the self-same end,

Does it delight her sometimes to employ

Severer interventions, ministry

More palpable, and so she dealt with me. [363-371]

Note carefully those last two lines, when he says that nature sometimes employs “severer interventions, ministry more palpable.” He is going back to what he said in those remarkable two lines, “Fair seed-time had my soul, and I grew up/Foster’d alike by beauty and by fear.” Here is the fear, the terror. Sometimes fear shaped him, as when he felt uncomfortable: It was wrong to trap birds, get bird’s eggs, steal from others’ traps. Fear teaches him ethics, morality. ‘This is wrong, and I learned that lesson from an early age.’

Now comes an astonishing memory, one which taught him – put simply – that stealing is wrong. Neither the simplistic ethical principle [Commandment 9: ‘Thou shalt not steal’] nor a fear of ‘doing wrong’ should obscure how remarkable is the episode he recounts.

Here it is in short. One evening he stole a rowboat to go on a late night adventure on a lake. [The episode is recounted in lines 372-426]. “It was an act of stealth and troubled pleasure,” he reports. Quite idyllic, rowing in the moonlight, his boat proceeding “Leaving behind her still on either side/Small circles glittering idly in the moon,/Until they melted all into one track/Of sparkling light.” (Lovely, isn’t it? Quite the opposite of what I at first believed, Wordsworth can write remarkable poetry.)

Here’s the thing to remember: When one rows a boat, unlike when one paddles a canoe, one faces backward and rows away from what one sees. He has his eyes on a hill, a “craggy ridge” on the horizon and rows toward the middle of the lake. In that small boat – “she was an elfin Pinnace” – as he proudly and assuredly rows, the boat “went heaving through the water, like a Swan,” when suddenly a mountain rears up behind the craggy ridge he is looking at. An ominous dark shape, “a huge Cliff,/As if with voluntary power instinct/ Uprear’d its head.” Still rowing with his back toward where he is going, he powers forward to escape this mass on the horizon; since he is rowing looking backward to where he has been, the more he tries to escape the huge mass that is arising, the more and larger the mass becomes.

I struck, and struck again

And, growing still in stature, the huge Cliff

Rose up between me and the stars, and still,

With measur’d motion, like a living thing,

Strode after me. With trembling hands I turn’d,

And through the silent water stole my way [408-413]

“Like a living thing.” The cliff seems to menace him, growing larger, until he turns around and heads back to land – and to the mooring place from which he had borrowed, well ‘stolen,’ the boat. This is, like the trapped birds, like the birds’ eggs, like the birds stolen from others’ traps, an instance where nature seemed to show him what was right. (We know, of course, that his already internalized sense of right and wrong indicated that stealing a boat was not right; still, it seemed like Nature was teaching the lesson.)

He learns the error of his ways, transfixed for days by terror.

and after I had seen

That spectacle, for many days, my brain

Work’d with a dim and undetermin’d sense

Of unknown modes of being; in my thoughts

There was a darkness, call it solitude,

Or blank desertion, no familiar shapes

Of hourly objects, images of trees,

Of sea or sky, no colours of green fields;

But huge and mighty Forms that do not live

Like living men mov’d slowly through the mind

By day and were the trouble of my dreams. [417-426]

Those “unknown modes of being” were the ethical laws – thou shalt not steal – that were imprinted on his brain and, by the power of nature and instinct, were deeply and profoundly ratified for him. If one is not ethical, one will live in “solitude…blank desertion” where “huge and mighty Forms” trouble consciousness. These forms trouble all of us, creating that ‘fear and trembling’ which is the continuous undertone or counterpoint to our adult lives.

Now we know, you and I, that we learn ethical laws when we are taught them by other human beings. ‘Thou shalt not steal.’ But I think what Wordsworth is recognizing here is that these ethical imperatives get a deeper dimension as we age: They become internalized and filled with immense power to shape our behavior. He borrowed a boat without permission – kind of stealing – and for days he was tormented by “huge and mighty Forms.” So, in each of us, the simple lessons of morality become enlarged, troubling us when we do ‘wrong.’ What Freud called the ‘superego’ forms out of early prohibitions, which in Wordsworth’s view are later ratified by experience. The superego is an internalized set of things we ought and ought not to do. We call it a conscience, a code of behavior, an ethical imperative. It is not the rules themselves, but our experience of them working in the world and in our lives, that matters. But is not conscience alone. This Kierkegaardian backdrop (‘fear and trembling’ is the Danish philosopher’s phrase) remains within us from childhood on. It is our constant, deep, companion.

I should note that Wordsworth (and this is important) does not go back to true infancy, for our memories do not encompass remembering that, although what is imprinted then, our earliest relations to others, our bodies, the world, shapes all that comes after. For him, childhood is that period from when he was eight or so until he was twelve or thirteen: That he does remember, and those days he recounts in this first book of The Prelude. We can perhaps see, in his awareness that fairly early experiences shaped his life and emotions ever afterwards, an even deeper awareness that yet earlier experiences would likewise have a shaping power.

Consider what he writes after that experience with the rowboat.

thus from my first dawn

Of Childhood didst Thou intertwine for me

The passions that build up our human Soul,

Not with the mean and vulgar works of Man,

But with high objects, with enduring things,

With life and nature, purifying thus

The elements of feeling and of thought,

And sanctifying, by such discipline,

Both pain and fear, until we recognise

A grandeur in the beatings of the heart. [432-441]

Whew. Early experiences, particularly of Nature (“enduring things”), shape our emotions; not superficiality or dross, but “purifying…and sanctifying, by such discipline,/Both pain and fear, until we recognize/A grandeur in the beatings of the heart.” Pain and fear are what he felt at the just concluded ‘rowboat’ episode; the residue of that experience is not just a sense of the ethical inclination of the universe, but deeply rooted sense of who he is. Who would not want to feel, to recognize, “a grandeur in the beatings of the heart”?

[It will take us until Book 11 for the reader to encounter what to me is one of the most meaningful passages in the entire work, where he writes of “spots of time.” (I am probably being too scholarly here, but this passage, and the two incidents following it that he recounts in order to illustrate these ‘spots of time,’ were actually in Book One of the 1798 Two-Part Prelude.)

There are in our existence spots of time,

Which with distinct preeminence retain

A renovating virtue, whence, depressed

By false opinion and contentious thought,

Or aught of heavier or more deadly weight

In trivial occupations and the round

Of ordinary intercourse, our minds

Are nourished and invisibly repaired— [ Book 11, lines 257-264 ]

I will write more about these specific spots of time later, in their proper place. Suffice it to say, for now, that the rowboat episode is one of them. By returning to what shaped him, he is “nourished and invisibly repaired.” That is, he anchors himself, by going back to the past, in events that shaped and created his self. He, confused as he was when he started the poem, is now firmly rooted in himself. I cannot emphasize strongly enough this strategy of finding the ground on which the self was formed, the ground on which in some sense the self still stands, as a way to encounter and accept the self.

In any case, Wordsworth proceeds to recall childhood, wandering through the fields and woods, ice-skating, flying kites, nutting, fishing, doing arithmetic, playing cards indoors. These experiences, recalled, are in the 1805 Book One, preceded and concluded by two important passages. The first (line 493) suggests that the “ministry’ of nature impressed upon him the glories of being alive, “and thus did make/The surface of the universal earth/With triumph, and delight, and hope, and fear,/Work like a sea.”

Then, later, he writes one of the most beautiful passages ever written:

how I have felt,

Not seldom, even in that tempestuous time,

Those hallow’d and pure motions of the sense

Which seem, in their simplicity, to own

An intellectual charm, that calm delight

Which, if I err not, surely must belong

To those first-born affinities that fit

Our new existence to existing things,

And, in our dawn of being, constitute

The bond of union betwixt life and joy. [576-585]

Yes, our earliest days – for those of us who are lucky, which I fear is not everyone – bring throughout life a “calm delight” which results from fitting ourselves into existence, those “first-born affinities…/in our dawn of being, constitute/The bond of union between life and joy.” Note what is happening here: The developing self, who we are and who we become, has its origin in the ‘affinity’ we feel towards the world we are born into. We fit ourselves into the world, “fit/ Our new existence to existing things.” We have an affinity for the world, and fit ourself into it.

And that fitting, that merging of self and world, is joyful. That life encompasses joy, that joy is part of what we know of being alive, comes from our earliest years, from sensing as children that there is a “union’ between life and joy which results from the emergent self recognizing it belongs in the world it has entered. (“I too was cast from the float forever held in solution,” Whitman wrote in “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry.”) Had Wordsworth written no more than the lines above, he would have been a major poet, one of the world’s great apostles of hope.

Children just do this, drink in joy and satisfaction from the world (or the mother’s breast, as we in our modern frankness, recognize).

A Child, I held unconscious intercourse

With the eternal Beauty, drinking in

A pure organic pleasure from the lines

Of curling mist…. [589-592]

Note the unconsciousness, the organicism. The world is like this, he says, and children, without the tools of adult thought, know it. The “unconscious intercourse” that results in joy comes to us as

that giddy bliss

Which, like a tempest, works along the blood

And is forgotten; even then I felt

Gleams like the flashing of a shield; the earth

And common face of Nature spake to me

Rememberable things; [611-616]

I can’t tell you how often I go back to these final two lines, which I say to myself at least once a week: “Nature spake to me/Rememberable things.” Whew. For me, when I recall and restate this line, it is not always ‘Nature,’ for it is often things we remember, which speak to us across decades. It was not Nature, exactly, that spoke to him from the rowboat episode: It was his memory of encountering the sublime. Still, what Wordsworth says is, I think, deeply true: What we experienced long ago keeps speaking to us or appearing to us in memory. Those long-ago experiences are “rememberable things,” and they mark us as who we are. As our own selves.

He goes on to say that these early experiences come to us when we are mature, when we are in need of reminding what life is, what joy feels like. “Doom’d to sleep/Until maturer seasons call’d them forth/To impregnate and to elevate the mind” [622-624].

He would later in his life write a poem that drew on this sense that earlier memories sustain us when life weighs us down. It is perhaps the most loved and cited poem in the English language, although it seems to sophisticates almost mawkishly sentimental. Except, except, that it recognizes that we are sustained by memories of joy.

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o'er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the milky way,

They stretched in never-ending line

Along the margin of a bay:

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.The waves beside them danced; but they

Out-did the sparkling waves in glee:

A poet could not but be gay,

In such a jocund company:

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

What wealth the show to me had brought:For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

The poem sure is sentimental, and the octosyllabic lines with their easy rhymes – ABABCC – lull us into a sentimental world, where daffodils bloom. But two things are happening here. First, the poet is sort of unconscious or at least not volitional when he sees the daffodils -- “I wandered lonely as a cloud” – “drinking a pure organic pleasure.” Second, and this in my view redeems the poem, he lies “in vacant or in pensive mood” in civilized and adult surroundings: That couch. And he is no longer vacant or depressed, for his “inner eye” recalls those daffodils blooming organically besides the lake. Remember that line from The Prelude, the “common face of Nature spake to me/Rememberable things”? Things that are “doom’d to sleep/Until maturer seasons call’d them forth/To impregnate and to elevate the mind” ? That is what is happening in “I wandered lonely as a cloud,” and what the whole of The Prelude is about: Recovering those memories, deeply etched into his consciousness, which can sustain him as he faces his writer’s block, his loss of imaginative powers.

As one reads the whole of The Prelude one recognizes how much of it has to do with the French Revolution: How it excited him greatly until its excesses, coupled with Britain’s failure to support its egalitarian aims, left him in deep despair. If we go back to Lyrical Ballads, and read his first completed meditative poem, “Tintern Abbey,” we recognize that it also seeks to recall a moment of joy to sustain him in his city existence, a moment that can provide sustenance five years after the joyous interlude in his life occurred. “Tintern Abbey” too was written in his despair over the failure of the French Revolution, and it appeared just one year before he wrote “The Two-Part Prelude.” Loss and recovery, be it politics or the living in the city or growing older, is Wordsworth’s great theme: One moves forward by going back and rooting oneself in one’s own life.

Having recounted much of his childhood – “I began/My story early” [640-641] – it is time for Wordsworth to end his first book, and he begins extricating himself. He defends having dwelt on childhood memories, which by itself might seem either self-indulgent or sentimental or both, for he recognizes returning to childhood can also serve as both a grounding and an inspiration. Note the “invigorating” in the passage below:

Meanwhile, my hope has been that I might fetch

Invigorating thoughts from former years,

Might fix the wavering balance of my mind,

And haply meet reproaches, too, whose power

May spur me on, in manhood now mature,

To honorable toil. [648-653]

Then he concludes, once again referring to Milton as he did in the opening lines,

One end hereby at least hath been attain’d,

My mind hath been revived, and if this mood

Desert me not, I will forthwith bring down,

Through later years, the story of my life.

The road lies plain before me; ’tis a theme

Single and of determined bounds; and hence

I chuse it rather at this time, than work

Of ampler or more varied argument. [664-671]

There is so much in these lines! He says the theme, his own history, is single and of determined bounds. True, the freedom to write about anything, anything at all, that so hampered him at the start is ended, and he has one theme – the development of his self – that is “of determined bounds.” But the choice is fateful: The origins and development of the self is the great theme of modernity, far more ample and varied than his ironic words are ready to acknowledge. (I recently quoted this passage about “single and of determined bounds” to my friend Paul Orgel, in an email discussion of Scarlatti, a great composer who limited his composing to brief harpsichord sonatas. Like Scarlatti, Wordsworth chose a single, defined ‘theme;’ unlike Scarlatti, his theme broadened and broadened until it contained more than could be imagined.)

Protagorus, one of the pre-Socratic philosophers, famously said, “Of all things the measure is man, of the things that are, that they are, and of things that are not, that they are not.” Much has transpired since then, but the return of the human as the center of things has returned. For Wordsworth it is the self, and the self’s development. For Freud it was the development of the ego. Even for Einstein, it was the centrality of the observer. Today, alas, it too often leads towards a self-indulgent narcissism, which is a terrible but consequential outcome of what Wordsworth began.

Wordsworth lived at the cusp of this new age of the self, and he was, it seems to me, its most telling prophet.