Constantine Cavafy, “Comes to Rest”

Many years ago I encountered the notion that T. S. Eliot greatly admired the Greek poet Constantine Cavafy. Not liking Eliot’s influence on poets and readers, I filed that away and read other poets.

Then, teaching a course in the ‘poetry of witness,’ I encountered Cavafy’s poems directly. He is not, except in very large terms, a political poet. He is, I discovered, one of the great poets of modernity. One of the great poets, period.

What Cavafy witnesses, what he testifies to, is the life of gay men.

William Wordsworth, “The world is too much with us”

“Wordsworth” always reminds me of my own past.

I started out intensely disliking William Wordsworth. I took a course, in college, in Romantic Poetry. Keats impressed me, Shelley too. Byron was a bit too ironic and comic, but then I thought (likely in error) that he was not a poet of the very first rank. I did like Coleridge, though I wasn’t sure why.

Wordsworth stuck in my craw. He was not as melodious as Shelley, not as finely crafted as Keats. There was something, well, prosaic and even preachy about his poems. Often they struck me, especially the early Lyrical Ballads, as simplistic.

A.R. Ammons, “Corson’s Inlet”

I left Washington at the end of 2012. Bernie had just been re-elected, the end of year-long lame-duck session was over, a new Senate was about to be sworn in. I had originally come to Washington for a year, maybe two, and ended up staying six years. I had started out doing legislative work on education and serving as a senior advisor to the new senator. For the past four years, I had been his Chief of Staff. Washington may be the center of a lot of political action, but it is a demanding place to work. I was tired and in need of a change.

I took some time off, tried my hand at detective fiction, and then returned to teaching.

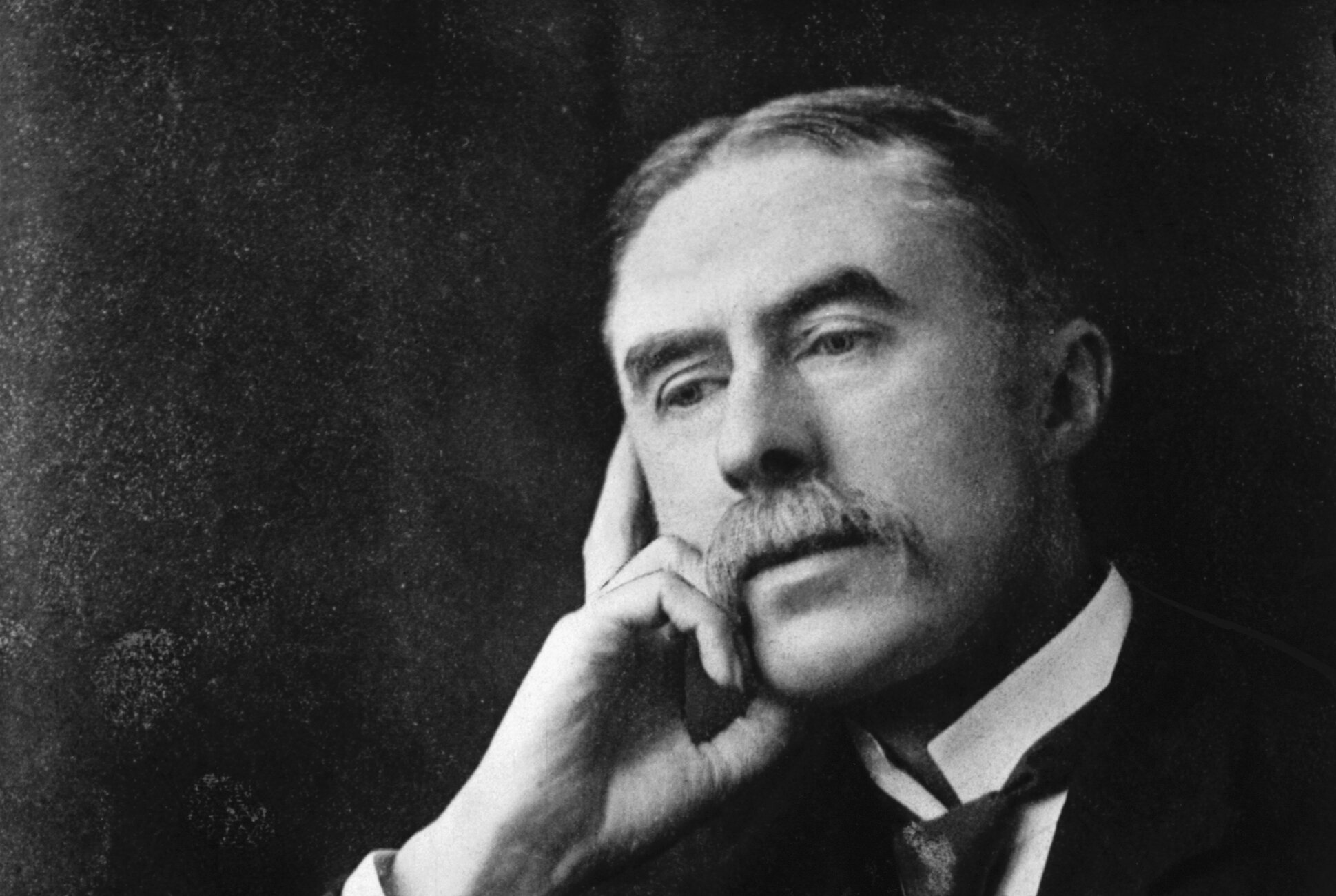

A.E. Housman, “Terence, This is Stupid Stuff”

I wrote an introduction to this poem, which follows:

Gerard Manley Hopkins in one of his late sonnets, addressed his writers’ block. (No, I have not had writer’s block). His concluding four lines are one of my favorite passages, lines I recite to myself often:

Zbigniew Herbert, “The Envoi of Mr. Cogito”

I wrote most of this essay as part of my ‘teaching’ in an introductory poetry class. When I sent it by email to my poetry list, I explained how I had come to write about a second poem by Zbigniew Herbert. (The first poem I sent out, which is the second letter about a poem on these pages, was Herbert’s “Five Men.”)

Let me offer two brief explanations to illuminate what follows. The first is easy: I originally wrote to my students, and as you who are reading this know by now, I think poems shed light on other poems. We live in a wonderfully interlinked network of texts.

Charles Ives, “The Things Our Fathers Loved”

Of all the essays in this book, this was the hardest to write. It took me a month. And even then, I was not satisfied with the result.

In good part that was because, although I love music, I don’t know how to analyze it with the same surety I bring to poems. I don’t play any instrument. I can’t read music. When I took several music courses decades ago in college, I was by far the least musical person in the class.

I first encountered this poem in a biography of the American composer Charles Ives. I didn’t think very much of it, but owing to the wondrous capacity of Spotify to bring to my computer speakers any kind of music I want to listen to, I played the song for which it provided the text.

Gwendolyn Brooks, “We Real Cool” and “The Chicago Defender Sends a Man to Little Rock”

When I returned to re-read this essay, I was struck by how ‘ethical’ its orientation was. I began the essay in Washington, focusing on a line that has always been terribly important to me. But I got hung up, as I acknowledge in the essay, by a stanza I did not understand in the longer poem. Thus, what I had to say about Gwendolyn Brooks lived in my computer’s files and not in the world beyond that.

Two things drew me back to this endeavor of addressing Gwendolyn Brooks. The first was that I taught “We Real Cool” in an introductory poetry course and had, as I was preparing to present it in class, what I might call an epiphany.

Seamus Heaney, “Singing School: 4. Summer 1969”

Over four decades, I turned from teaching contemporary literature to teaching older literature, primarily from the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century.

Partly, it was because ‘contemporary’ works kept coming out, and it was hard to keep up when the ‘field’ was constantly changing.

More importantly: as crucial as it is to get a sense of perspective on our own times, it is also immensely difficult and at times even impossible. The most important Romantic poet? Wordsworth. The greatest second-generation Romantic? Keats. The most important poets in English of mid- and later nineteenth century? Whitman and Dickinson. The most important poets of modernism writing in English? Yeats, Williams, Eliot, Stevens, maybe Frost. The most important poets of the next generation? Auden and Bishop. The most important poets of the post-war era? Lowell and Plath.

See? It’s easy. And even if some might disagree, the disagreements can readily be accommodated.

But the best or most important poet of our times? Hard to say.

Charles Baudelaire, “A Rotting Corpse”

A narrative about a man in a black leather jacket:

My friend Luther Martin and I had invited a famous French scholar to come to the University of Vermont to teach a seminar for faculty. Intrigued by our offer, he agreed to discuss it when he came to a conference in southern California, so Luther and I flew there to meet with him.

The conference on his work, which we thought would draw a few dozen participants, drew many hundreds of attendees. Our chosen scholar was, it turned out, an academic and cultural superstar. Everyone wanted to talk with him and spend time with him.

Vladimir Mayakovsky, “At the Top of My Voice”

This mailing was very long. It considered a six-page poem and it includes the poem – twice. The poem, Vladimir Mayakovsky’s “At the Top of My Voice,” is exuberant, fun, and not (with one exception) very difficult. I hope you will embark on it with pleasure and without being dissuaded by its length.

As for the one difficulty: it has to do with Mayakovsky’s transgression of what we expect of a poet’s ‘voice.’ Before entering the poem let us consider how his use of radically different (and I think joyously exciting) multiple voices makes the poem extra-ordinary.

Dickinson and Wordsworth: Spring Poems: “I dreaded that first robin so” and “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud”

Vermont is in full spring as I write. The crocus and scilla have blossomed and are gone, the daffodils are fading, the tulips are in full bloom. Cherry and apple and pear are a riot of blossoms. The trees are leafing and flowering, reminding me as always that as Robert Frost wrote, “Nature’s first green is gold.”

It seems appropriate, then, to consider a spring poem. I will, in fact, consider two, one by Emily Dickinson, one by William Wordsworth.

James Dickey, “The Bee”

Dickey was born in Atlanta, where he lived until he enrolled at Clemson College in 1942. He was a tailback on the football team there, an experience of central importance to “The Bee.” When America entered World War II. he dropped out of Clemson after one semester to join the Air Corps. He served as a navigator in the Pacific Theater.

Maxine Kumin, “How It Is”

I sent out a poem by James Dickey, “The Bee,” which was about maleness, about fathers and sons, about being a jock, about the continuity of life. Here is a poem by Maxine Kumin which might be called a polar opposite, since it deals with friendship that borders on sisterhood, since it is about women, since it deals with death rather than life. Both poems, opposite as they are, focus on the ongoing relations between human beings and the importance of those relations.

Zbigniew Herbert: The Utility of Poems, “Mr Cogito Reads the Newspaper”

I wrote this letter when I was deeply troubled by the world, and in particular the ongoing war in Syria and the refugee crisis it engendered. I spoke in my class on poetry about the situation in the world. I gave them so grievous facts about the historical place we are living in. Those facts come at the end of this essay.

Rilke, “Ninth Duino Elegy”

This was a very long mailing. That seems to me appropriate, since it is on what I consider to be one of the very greatest of all poems, Rainer Maria Rilke’s “Ninth Duino Elegy.” The poem itself is two pages. I take it up as I usually do, line by line, stanza by stanza. So just printing the poem twice takes up four pages.

Philip Larkin, Three Poems: “This Be the Verse,” “Mower,” and “Aubade”

Philip Larkin is not a poet of the vernacular, though he uses it often enough. But I have found, in recent years, that reading him is like a salutary dose of directness in a world where too often circumlocution, avoidance and outright lies seem to hold sway. I did not always love Larkin: I read his Collected Poems and was relatively unmoved. ‘Ah,’ I thought, ‘those Brits like their poets narrow and pedantic and unadorned.’ I should have known better – that ‘unadorned’ is something that usually attracts me.

Matthew Arnold, “Dover Beach”

It is a story worth remembering, though it seems to have faded from memory. Lyndon Johnson, in the midst of the war in Vietnam, decided to hold a ‘Festival of the Arts.’ One of the invitees was poet Robert Lowell, and he was not just invited: he was asked to speak, along with novelists Saul Bellow and John Hersey and critic Dwight MacDonald. Lowell, after first accepting the invitation, quite publicly declined it.

On the Limits of the Imagination

We come back and back again to the same old questions.

Because imagination is so important to both writing and the study of writing we praise the imagination as essential to the creation of narrative, poetry and all structured language. We, creators and readers alike, have a great stake in how powerful our engagement with human creativity is.

Gerard Manley Hopkins, “No Worst, there is none”

Emily Dickinson began a poem, “Tell all the truth but tell it slant – /Success in Circuit lies.” Sometimes, as she recognized, we need to work our way into truth, since it can be terribly painful and cannot be addressed straight out. This poem is about pain and how difficult it is to bear. We will work out way towards this awful recognition, slant-wise.

Guillaume Apollinaire “The Little Car”

I initially wrote about Guillaume Apollinaire’s wonderful poem, “The Little Car,” and then hesitated to send it out, because, as I acknowledge at the outset and again at the end, it is not just about war, but about glorifying war. Yes, it says other things too; But in a world where nationalism and tribalism are rising, a world which too often seems to forget how destructive war can be, Apollinaire’s poem can be – well, it can tell us the wrong things.